It was a New Deal program that promoted old-fashioned housing discrimination and caused lasting damage to individuals and urban neighborhoods.

The 1934 National Housing Act revived the nation’s struggling construction industry and provided improved housing for tens of millions of Americans. Later, the Act – and the thirty-year mortgages it spawned – set the stage for America’s post-war housing boom. But the Act also encouraged redlining, a then-legal yet highly-discriminatory practice that denied mortgages to residents of thousands of urban neighborhoods. The results were predictably catastrophic. Today, fifty years after redlining was made illegal, its victims, their descendants, and the communities where they lived still suffer from its effects.

Redlining was the denial of financial services – including mortgages and insurance policies – to residents of targeted districts. Without access to federally guaranteed loans, residents of redlined neighborhoods were trapped in declining areas where jobs were scarce and industrial pollution was rampant. The practice denied them the opportunity to build equity and wealth, a generational penalty that is still being paid.

Redlining wasn’t specifically intended to destroy neighborhoods, though it was instrumental in the destruction of many. Its purpose was to protect mortgage issuers and the federal government from the risk of non-repayment. But rather than require lenders to carefully assess the financial status of each loan applicant, the government allowed financial institutions to deny loans collectively to all residents of designated districts. Worse, the federal government actually laid the groundwork for redlining by developing the maps that labeled some neighborhoods as safe for loans, and others as highly risky.

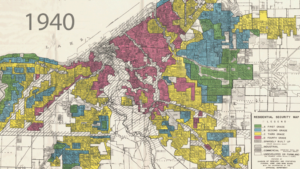

Federal ‘residential security maps’ were created for more than 200 American cities by the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC). These maps assigned each of a city’s neighborhoods one of four ratings: Type A – typically affluent neighborhoods on the edges of the urban area; Type B – less affluent, but still desirable neighborhoods; Type C – declining neighborhoods; and Type D – lower income neighborhoods, hazardous for lenders. On the maps prepared by HOLC, Type D areas were outlined in red – thus, redlining.

Map of the Cleveland Metropolitan District and Cuyahoga County, created by the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1940

Ratings were assigned based on demographics and other characteristics. Banks were eager to make loans in Type A and B neighborhoods. Some loans were made in Type C neighborhoods, but the terms were harsher than loans in better neighborhoods. Virtually no loans were made in Type D areas.

Neighborhoods with measurable numbers of African-American, Jewish, Asian, and Hispanic residents were nearly always assigned Type D. Not only were residents of these areas denied loans, but the rating itself lowered neighborhood property values. The fact that African-American residents caused a neighborhood to be redlined gave whites yet another reason to keep African-Americans out of their communities through zoning regulations, restrictive housing covenants, and, at times, threats of violence.

Redlining didn’t create racially segregated cities. By the mid-1930’s, African-Americans were already confined to inner city ghettos by prejudice and fear. But redlining gave housing discrimination a veneer of legality, if not moral authority, and it provided banks with a justification for discriminatory practices that effectively trapped African-Americans in overcrowded, decaying slums where they were easily exploited by landlords who charged excessive rents and made few repairs.

Redlining also denied African-Americans the benefits of federal housing policy from the 1930’s to the 1970’s, a period when the nation’s rate of home ownership jumped from under 50 percent to almost 70 percent. By the late 1950’s, fewer than two percent of FHA-guaranteed loans had been issued to minorities.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 ended legal redlining. But the effects of the practice are still felt, said Devonta’ Dickey, Advocacy and Engagement Coordinator for Cleveland Neighborhood Progress. Redlining and other forms of housing discrimination are significant factors in the disparity in wealth between whites and the victims of redlining.

In Cleveland, areas redlined on the HOLC’s 1940 map correspond almost exactly with areas that today suffer the highest rates of poverty, poor health, disinvestment, foreclosures, and toxic releases, Dickey said.

Discriminatory practices in Cuyahoga County didn’t end when redlining was made illegal. Research conducted in 2019 by the Western Reserve Land Conservancy’s Thriving Communities Program found that African American borrowers seeking home purchase loans are denied more than twice as often as Caucasian borrowers. Further, high income blacks are denied loans more often than moderate- and middle-income Caucasians.

February 28, 2020

References:

https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/national-housing-act-1934/

https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/national-housing-act-1934/

https://www.wrlandconservancy.org/articles/2019/07/31/housingmarketstudy/

Images:

Top image: House from redlined neighborhood in Cleveland, 1962; Cleveland Public Library

HOLC map: https://ohiohome.org/news/blog/october-2018/predictingevictions.aspx