Calls for major police reform are nothing new.

From Theodore Roosevelt’s efforts to reform the New York City Police Department in the late 1890’s, to President Lyndon Johnson’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice in the 1960’s, to President Barack Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing in 2014-2015, efforts to improve police professionalism, root out corruption, and improve police performance have been a constant feature of American law enforcement for more than a century.

But such efforts have always faced opposition, and while many police departments today are far more professional, diverse, responsive, and community-focused than in the past, problems remain.

Reform advocates and law enforcement leaders together recognize problem areas where reform is most needed, including accountability and transparency, excessive use of force, discriminatory stop-and-frisk practices, inadequate training, and police militarization. They also agree that significant police reform will require a community-wide effort. Law enforcement agencies will not be able to do it on their own, and community organizations will not be able to force change. Only a cooperative effort will result in sustainable and effective reform.

But today there is no national consensus on the need for reform, let alone for its direction. American law enforcement is highly decentralized – there are more than 18,000 separate police agencies in the United States – and many, if not most Americans believe their local police departments are effective.

Often, of course, this is the case. But many of the ills of modern American policing are hidden from view of most citizens. Americans in general – exposed to many decades of TV and movie cops, but almost totally unfamiliar with real police – have little understanding of how police in this country actually perform their jobs.

Police themselves are not much help. Law enforcement culture highly values secrecy, autonomy, forcefulness, and an us-versus-them worldview, hardly conducive to open discussion of police performance. Individual officers and their departments are loath to discuss the way they actually operate and the underlying beliefs that drive their behavior.

So, while many Americans seem to agree on the necessity for some police reform – The George Floyd video has had an enormous impact – there is much less understanding of what types of reform are really needed.

“I don’t think most people have any sort of fundamental connectedness to law enforcement, and I think we are at a place now where we are talking about making changes, but the average citizen has no clue of the foundation of how law enforcement works and what should be changed,” said Sophia Hall, Supervising Attorney at Lawyers for Civil Rights.

Hall was a panelist on a recent WGBH virtual forum on Police Reform, part of that station’s series of discussions on ‘The State of Race.’

A better understanding of law enforcement is necessary for an informed communitywide discussion of police reform, said fellow panelist Dominique Johnson, Senior Director of Community Engagement at the Center for Policing Equity. The conversation we need to have is about how do police departments work, said Johnson. “How do you engage people to understand and educate them around the systems of public safety so that they can make informed decisions.”

Calls for defunding the police are misleading and counter-productive, said panelist Milton Valencia, political reporter for the Boston Globe. “It’s not so much getting rid of police, it’s not so much getting rid of the police budget, its more reimagining what we do with our resources and where they’re devoted to,” said Valencia.

“Instead of 911 calls being automatically diverted to police systems… especially mental health cases, we need to look at other ways to redirect community social service programs so that it’s not always the police responding,” said Valencia.

Boston City Councilor Andrea Campbell said that ‘defunding’ the police does not mean abolishing police departments. “But it does involve reallocating a significant amount of resources from our police departments to programs, issues, and initiatives and individuals that are doing the work on the root causes of violence,” she said. “We have to focus on eradicating poverty, mental health, trauma support, jobs, economic opportunity, and there are a lot of programs and individuals doing this work who are struggling right now to find resources to do that work, and that’s just unacceptable when you think about our police department is over $400 million in terms of their budget and an overtime budget that’s over $70 million, and it keeps going up and you ask why?”

Police are called on to replace gaps in the nation’s social services safety net. But they are untrained and ill-equipped to provide the services that people need. The results can be disastrous, for citizens and the police. “Most Americans do not realize that nearly fifty percent of fatal police encounters involve a victim who is living with a mental health issue, with a disability,” said Hall.

It is important to remember that law enforcement problems are structural and systemic, said Hall. The blame for many problems with police performance cannot be laid at the feet of individual officers.

Ronald L. Davis, former Director of the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) in the Department of Justice, believes that reform efforts must focus on the operational systems that guide law enforcement. “Rank-and-file officers do not decide organizational policies and practices,” Davis wrote in 2016. “Nor do officers establish hiring standards or have the power to administer discipline. They also do not decide whether an agency embraces crime-reduction strategies that result in racial disparities. Yet when disparities or other systemic problems do occur, rank-and-file officers are quickly demonized and blamed for those outcomes. There is no question that rank-and-file officers must be held accountable for their actions. However, if the systems in which they operate are flawed, even good officers can have bad outcomes.”

“If we are to achieve real and sustainable reform in law enforcement,” continued Davis. “Our focus must shift from the police (those individuals sworn to uphold the law) to policing systems (the policies, practices, and culture of police organizations).”

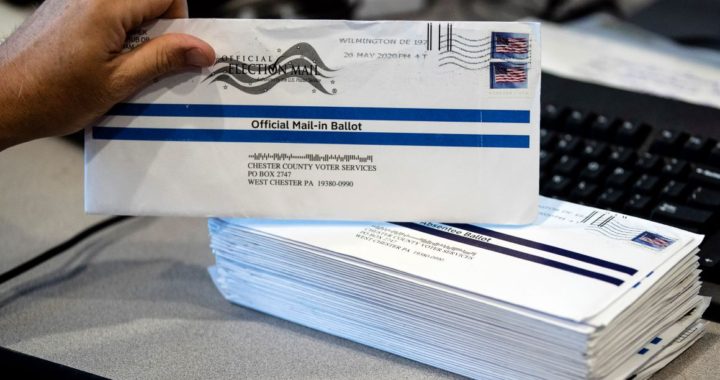

Despite difficulties, efforts at police reform are continuing. Voters in at least six states approved police reform measures in the election earlier this month.

November 23, 2020