They couldn’t quite kill it.

Oh, they tried. For forty years they looted it, wrecked it, and vandalized it. They even beheaded it. But somehow, the Anchor-Hocking Glass Company survived. The century-old manufacturer still makes high-quality glass products in their rusting old glassworks in Lancaster, Ohio. But though it escaped destruction, Anchor today is a pale reflection of its former self, and it no longer supports the middle-class aspirations of its workers or the community itself.

Anchor’s story is not unique. What happened to Anchor – and Lancaster – happened to a thousand companies and cities across America’s industrial heartland when a toxic wave of unconstrained greed, unintended consequences, selfishness, and corporate malfeasance swept away a century of corporate diligence and good citizenship.

“The new American economy had come to town like an unwelcome stranger,” wrote journalist Brian Alexander, “leaving Lancaster broken.”

Alexander chronicled the life and near-death of Anchor-Hocking and the city of Lancaster in his 2017 book: Glass House – The 1 Percent Economy and the Shattering of the All-American Town. He traced the damage to Anchor and the corresponding decline of Lancaster as the company and city staggered through a nationwide maelstrom of wrenching economic and social change.

A Sense of Community

For decades Anchor-Hocking was the largest employer and the most important corporate citizen of Lancaster, a tidy manufacturing town of 30,000 residents, located thirty miles from Columbus. Five thousand Lancaster residents worked for Anchor, including unskilled laborers, experienced craftsmen, supervisors, managers, engineers, and executives. Other industries called Lancaster home, but Anchor-Hocking – a nationally-recognized brand – was the pride of Lancaster.

The decades after World War II were a golden age for Anchor and American manufacturers in general. Pent up demand for consumer products and the lack of foreign competition boosted sales and revenue. There was money to go around and labor relations were cordial. By the late 1960’s, Anchor-Hocking was the world’s leading manufacturer of glass tableware and the second-largest maker of glass containers.

The city supported Anchor, and Anchor supported the city. Generations of workers found stable, good-paying jobs with the company. Those that stayed until retirement – and there were many – received a company-funded pension and health insurance. Anchor’s taxes supported the city and schools, while employees and their spouses were active in the community’s life. The business culture of the time fostered a sense of community. Anchor’s senior executives all lived in Lancaster, and they were committed to the city.

Cheap Stuff

In the 1970’s, though, the first signs of trouble appeared. Energy costs rose alarmingly, hurting American manufacturers. Food and beverage producers turned to plastic as a cheaper alternative to glass containers. Pressure from foreign manufacturers grew in the glass industry, as French, Polish, and Turkish companies began importing cheap glass into the U.S.

Anchor responded with traditional business practices – greater efficiency, higher quality, better marketing – and sales remained strong. While challenges remained, the company was well-positioned to continue as a profitable enterprise for years to come.

For years, American manufacturers had valued the quality of their products and their importance in their communities. By the 1980’s, however, the American business environment was changing. Anchor and thousands of other American manufacturing firms found themselves threatened by a devastating combination of foreign competition, relentless pressure to reduce costs, and sudden attacks by corporate raiders.

The consolidation of the retail sector into fewer, much larger companies reduced competition. Nationwide retailers began pressing manufacturers like Anchor-Hocking to reduce the price of their products. As the focus of retailers and consumers shifted to low-cost products, the pressure on American manufacturers to reduce costs grew.

“Americans wanted cheap stuff,” wrote Alexander. “And the harder they shopped for the cheapest stuff, the more they helped drive down the wages of people who made stuff. And the lower those wages dropped, the more a desire for cheap morphed into the self-fulfilling necessity of cheap.”

The growing demand for low, low prices inevitably drove American jobs overseas. No matter how efficient and cost-conscious Anchor-Hocking might be, no matter how low they drove the wages of their own workers, there would always be people somewhere else who could do the work for less.

“The knowledge of craftsmen was lost in order to make a product a little bit cheaper,” wrote Alexander. There was no room in the new business culture for concern about the workers that used to make the products that built the manufacturing companies in the first place, or for the communities where they lived.

A Duty

Pressure to cut costs didn’t come only from consumers. By the 1980’s, American business leaders had widely embraced “shareholder capitalism” – the idea that corporations existed solely to maximize shareholder profit. Previously, most corporate executives had practiced “stakeholder capitalism,” through which companies attempted to optimize the well-being of customers, employees, shareholders, and the nation.

Most prominently endorsed by economist Milton Friedman, ‘shareholder capitalism’ became Republican party orthodoxy in the 1980’s.

In a 1970 essay for the New York Times, Friedman rejected the idea that corporations had any responsibility to workers, their communities, or the nation. “There is one and only one social responsibility of business,” he wrote. “To use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception fraud.”

Alexander wrote, “The Friedman doctrine told every executive, financier and shareholder not only that it was okay to make a profit, but that making as much profit as possible, without regard to some broader social responsibility, was a duty.”

If a company could increase profits by shifting work overseas, by closing plants, by firing workers, by reducing the remaining workers’ pay or benefits, by halting research and development, by deferring maintenance, by forgoing needed upgrades, by neglecting safety, by using a lower grade of raw materials, by refusing to implement pollution control measures, or by declining to support community organizations, it had an actual duty to do so, according to Friedman.

“For generations, through both periods of harmony and episodes of friction, workers and management understood that their interests were aligned,” wrote Alexander. “Now they weren’t.”

Friedman served as a member of President Reagan’s Economic Policy Board, and his views were adopted by the federal government.

The government also supported the growing numbers of acquisitions, mergers, and corporate takeovers being conducted by large companies and private equity firms. It was a series of takeovers and purchases that crippled Anchor-Hocking and Lancaster.

It Was Being Killed

The first attempt to take over Anchor-Hocking was made by Carl Icahn, one of America’s most prominent corporate raiders and a firm believer in the Friedman doctrine. Icahn believed that American corporations had become inefficient and lax in their ability to provide dividends and profits to investors.

Icahn and other ‘raiders’ of the era gained control of companies through stealthy stock purchases using borrowed money, then used their ownership stake to obtain seats on corporate boards and impose savage “reforms” to maximize the short-term value of the company’s stock. Once the value of the company had been inflated at the expense of the firm’s long-term stability, raiders would sell their shares, pocketing large profits.

Icahn’s attempt to gain a seat on Anchor Hocking’s board ultimately failed. The company bought him off by repurchasing his stock at a premium – an attempt at self-preservation called, fittingly, greenmail. Icahn scored a $3 million profit and Anchor-Hocking escaped his clutches. But that was $3 million that the company could not use to pay workers, improve products, or update equipment.

“It was,” said one of Icahn’s analysts, “like taking candy from a baby.”

Worse, Icahn’s attack signaled to other raiders that Anchor-Hocking was a viable target. While Anchor was able to fend off Icahn, they could not protect themselves from follow-on attacks by ownership groups that hoped only to boost the value of the company and sell it, pocketing the profits.

Over the next thirty years, a succession of absentee owners would sell off portions of Anchor-Hocking, drive the company into bankruptcy, slash employment in Lancaster from 5,000 to 1,000, move the corporate headquarters with its hundreds of well-paid executive jobs out of the city, reduce pay for workers, stop contributions to the workers’ 401K accounts, drastically raise health insurance premiums paid by workers, drop health insurance for retirees, defer critical maintenance, and destroy the company’s relationship with Lancaster. Yet each change in ownership resulted in additional profits for investors.

“Anchor Hocking wasn’t dying a natural death,” wrote Alexander. “It was being killed.”

As out-of-town ownership stripped the company of assets, fired workers, and drained the company’s coffers, city officials responded by offering incentives to the company – in effect, bribes – to stay open in Lancaster. City officials offered a series of tax abatements that reduced funding for public schools, the city, and the county. They also gave the owners a 55 percent tax credit and $100,000 to train fifty new workers, after the company had shut down its own apprenticeship program that had been providing skilled laborers for decades

The decline of Anchor was devastating for Lancaster. The city seemed to lose confidence in its future – the citizens seemed to pull back. In 1988 a school property levy was defeated. In 1989, the school board tried to pass a small income tax increase to fund schools. That failed, too, so did road improvement taxes and bond levies. Drug use rose, then skyrocketed.

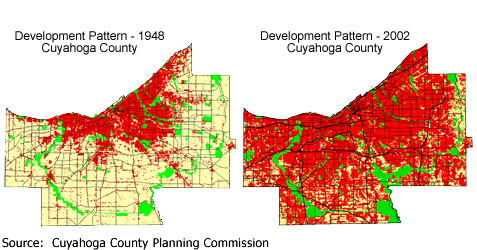

It was a scenario replayed in thousands of American cities.

Catastrophic for America

The impact of ‘shareholder capitalism’ has been catastrophic for America, said Peter Georgescu, former chairman of Young and Rubicon, a global marketing and communications company. Profits have soared at the expense of worker pay, he wrote in his 2017 book, Capitalists Arise!

Wealth of the median American family is lower today than two decades ago while life expectancy has actually fallen, he wrote. While real wages have been flat for decades, American productivity has increased by 80 percent. Before the 1970’s wages and productivity had always risen in tandem, as workers shared in the rewards of greater productivity. Now, however, most gains from productivity flow to shareholders, not workers.

As distant ownership of countless American manufacturers broke labor contracts and reneged on long-standing promises regarding pensions, health care, benefits, and the future of the company, workers and the communities around them lost faith and trust in the companies, wrote Steven Pearlstein in his 2018 book, Can American Capitalism Survive? Disheartened workers became less productive, less efficient, and less innovative.

A growing number of business leaders, like Georgescu, are calling for a return to stakeholder capitalism and a rejection of the shareholder-profits-above-all philosophy of Friedman and others. In 2019, nearly 200 senior American business executives, including the leaders of Apple and JPMorgan, signed a statement pledging to shift their business focus from maximizing shareholder value to providing value to all stakeholders, including investors, workers, customers, and suppliers.

But investors are resistant, and the future of American capitalism is unclear.

Ribbons of Glass

For millions of American workers who have lost their jobs, and thousands of American cities that have been hollowed out by greed, any reversion to a more socially-responsible form of capitalism will be too little, too late.

The collapse of American manufacturing wasn’t caused by local politicians, or the national media, or by a failure of work ethic among young workers, wrote Alexander. “It came from a thirty-five-year program of exploitation and value destruction in the service of ‘returns.’ America had fetishized cash until it became synonymous with virtue.”

What’s remarkable about Anchor-Hocking is that it somehow still survives. Despite decades of neglect, asset-stripping, and corporate malfeasance, ribbons of molten glass still flow from furnaces where the temperatures reach 2700 degrees F; glassmakers still run massive stamping machines in the 120-degree heat of the factory; and the company still produces tumblers, bowls, pitchers, and other glassware for customers across the nation. More than 1,000 workers still have jobs at Anchor-Hocking, though their wages are low and benefits are limited.

And Lancaster? While the city’s industrial base has been decimated, more and more residents are commuting to jobs in the Columbus area. Much of the work that remains in the city is low-wage, and city efforts to attract new industries have largely failed, but the population is stable and the city’s transition to a bedroom community has protected it from the worst ravages of de-industrialization.

February 25, 2021

For more information, see also:

Alexander, Brian; Glass House: The 1 Percent Economy and the Shattering of the All-American Town; St. Martin’s Press, NY; 2017.

Georgescu, Peters and Dorsey, David: Capitalists Arise; Berrett-Koehler Publishers; Oakland, CA; 20217.

Pearlstein, Steven; Can American Capitalism Survive: St. Martin’s Press, NY; 2018.

Retrieved 2.22.2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/19/business-roundtable-ceos-corporations.html

Retrieved 8.17.2019

Retrieved 2.25.2021