While the large-scale demonstrations against police killings of unarmed men have ebbed, the underlying causes of the protests remain. Too many Americans, especially persons of color, remain suspicious and distrustful of police. In their eyes, police are rarely held accountable for their mistakes or misconduct, even when those errors cost the lives of innocent persons.

Accountability is an issue that has bedeviled law enforcement administrators, municipal leaders, community activists, and sociologists since the 1960’s. Police have done themselves no favors with their knee-jerk opposition to any attempt to hold officers or departments accountable for misconduct. Though in some ways understandable, the reluctance of police agencies to hold members accountable for errors is enormously counterproductive.

Law enforcement agencies that refuse to hold their members accountable can break the essential links between police and the communities they serve. Lack of accountability erodes public trust and fosters suspicion and resentment. Citizens who distrust the police are less likely to provide information or other assistance that could help police in their efforts to reduce crime. Most people understand that law enforcement is difficult, demanding, and dangerous, but they also expect that when an officer makes an error – especially an error that results in the death of an unarmed citizen – that some corrective action will be taken.

Many police chiefs and top administrators recognize the damage that denying misconduct and protecting officers from accountability is doing. So do many – if not most – rank-and-file police officers. Given a choice, the vast majority of police officers would prefer that all of their colleagues behave professionally at all times.

But police culture today is a powerful impediment to police accountability. The culture of law enforcement is all-enveloping, and law enforcement officers highly value the camaraderie and sense of belonging that membership in the police “fraternity” bestows. Unfortunately, many elements of law enforcement culture are antithetical to accountability, including an ‘us versus them’ mentality, a high regard for autonomy, a commitment to secrecy, and a feeling of solidarity with members of their own organization.

Establishing a culture of accountability must focus on organizational changes, rather than on the actions of individual officers. The problem is systemic, and attempting to place the blame for misconduct on ‘a few bad apples’ are doomed to fail. Many police agencies have taken steps to increase accountability, including the creation of police review boards, early intervention systems, improved citizen complaint procedures, external review of critical incidents, additional restrictions on the use of deadly force, better employee evaluation systems, higher educational standards for new hires, more comprehensive training, and greater emphasis on community-oriented policing.

Not all of these steps can be effective in every department, and research to identify the most effective practices continues, but while it might not be apparent to the casual observer, overall police accountability is greatly improved since the 1960’s.

But despite progress, problems remain. Like civil aviation, medicine, and other professions, the margin for error in law enforcement is razor-thin. Mistakes can be uncorrectable and the consequences can be irrevocable.

Efforts to increase police accountability shouldn’t be viewed as threatening or hostile by police officers and their most ardent supporters. Greater transparency and a good-faith effort to hold departments and individual officers accountable for their actions are in the best interests of police and citizens alike.

“I know being a cop is hard. I know that shit’s dangerous. I know it is, okay? But some jobs can’t have bad apples. Some jobs, everybody gotta be good. Like pilots. Ya know, American Airlines can’t be like, ‘Most of our pilots like to land. We just got a few bad apples that like to crash into mountains.’

– Comedian Chris Rock

January 1, 2019

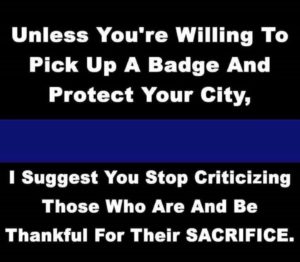

While eerily reminiscent of COL Jessup’s unhinged testimony in A Few Good Men, this post reflects an attitude that might not be as helpful as some posters believe.

While eerily reminiscent of COL Jessup’s unhinged testimony in A Few Good Men, this post reflects an attitude that might not be as helpful as some posters believe.