As American military forces converged on the Mariana Islands in the summer of 1944, Japanese Navy admirals understood what was at stake. Loss of the islands of Guam, Saipan, and Tinian would leave the Americans in possession of airfields within B-29 bomber range of Japan as well as naval bases for deadly U.S. submarines. The Marianas had to be defended.

Since its crushing defeats at Midway and in the Solomons in 1942 and 1943, the Japanese Navy had concentrated on rebuilding its strength and preparing for the ‘decisive battle’ that Japanese strategists believed would decide the Pacific War. Now that battle was upon them in the Philippine Sea.

But when it came, the ‘decisive battle’ was a disaster for the Japanese. Poorly trained pilots in increasingly obsolete aircraft were massacred by highly-trained Americans flying newer, more advanced planes. Japanese aircraft that managed to escape American fighters were met by a storm of anti-aircraft fire from Pacific Fleet ships. The air battle that was fought on June 19-20 1944 was such a mismatch that American pilots called it a ‘turkey shoot.’ The Japanese lost more than 500 planes; the Americans fewer than 130. Three Japanese aircraft carriers were sunk – two by U.S. submarines – but six others escaped.

While some American officers fumed at the escape of the enemy carriers, Japanese naval leaders understood the true scale of the catastrophe. Carrier decks were useless without skilled aviators to fly from them, and the loss of hundreds of irreplaceable Japanese pilots signaled the end of the Imperial Japanese Navy as an effective fighting force.

“Though Americans were slow to appreciate it,” wrote American historian Ian W. Toll, “they had just won the decisive victory of the Pacific War. Capture of the Marianas and the accompanying ruin of Japanese carrier airpower were final and irrevocable blows to the hopes of the Japanese.”

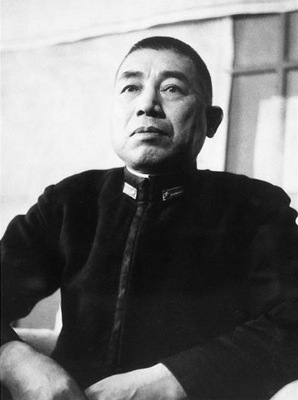

The loss of the Marianas, a stinging defeat in India, the dogged refusal of the Chinese to capitulate, and the terrifying prospect of B-29 raids against the home islands shocked the Japanese leadership. The loss of Saipan, home to more than 20,000 Japanese colonists, was the first indication to the Japanese public that the war was being lost. Following the fall of Saipan, Hideki Tojo was forced to resign as Japanese prime minister.

Special Attack Units

Japanese Navy leaders searched frantically for a way – any way – to slow the American advance. Facing overwhelming American industrial and military power, with their own fleet tethered to their last sources of fuel in the East Indies, and with American submarines tightening their stranglehold on Japan’s maritime supply lines, Japanese admirals believed that their only chance to avoid catastrophic defeat was to inflict such horrific damage on American forces that the United States would accept some form of negotiated settlement.

But it was clear that the battered Japanese Navy – especially its toothless carrier striking force – would never be able to deliver such a blow. So, slowly, a controversial idea that had not been contemplated in earnest before became a serious consideration.

If conventional air attacks could not succeed, what about unconventional attacks? Could the unsurpassed fighting spirit of the Japanese overcome the massive material and technological advantages of the United States? Japan had plenty of planes, but hardly any skilled pilots. Training pilots took time and fuel that Japan didn’t have. Was there a way to increase the effectiveness of untrained pilots?

It appeared to some that there was.

“No longer can we hope to sink the numerically superior enemy aircraft carriers through ordinary attack methods,” wrote Japanese Navy Captain Eiichiro Iyo, who had commanded the Japanese light carrier Chiyoda at Philippine Sea. “I urge the immediate organization of special attack units to carry out crash-dive tactics and I ask to be placed in command of them.”

Iyo was not the first Japanese officer to recommend creation of suicide units. The concept had been discussed by senior Japanese military leaders as early as 1943, and was familiar to many pilots. Recognizing the dire circumstances Japan was facing, some officers declined to wait for senior-level approval.

In May 1944, before the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Japanese Army Major Katashige Takata, commander of the Fifth Army Air Squadron at Biak Island in New Guinea, led a group of volunteer pilots on a suicide mission against U.S. invasion shipping. One aircraft managed to damage a U.S. subchaser.

In July, while Japanese Navy leaders considered the question of adopting suicide tactics, Captain Kanzo Miura, commander of a Japanese air wing at Iwo Jima, shocked his pilots by ordering them to make suicide attacks against U.S. ships. No American ships were damaged in this attack.

On 15 October, in the Philippines, Rear Admiral Masafumi Arima personally led a strike against U.S. ships. Against the protests of his staff, Arima removed all insignias of rank from his uniform, indicating that he did not intend to return. He did not return, but U.S. Navy records do not report any successful suicide attacks that day.

So, it was no surprise when Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi, newly installed as Commander of the First Air Fleet in the Philippines, told his subordinates that the only chance the Japanese had to defend the Philippines was to make suicide attacks against American aircraft carriers. Onishi took the idea of creating units of specially-trained suicide pilots to his superiors.

“In my opinion,” he wrote, “there is only one way of assuring that our meager strength will be effective to a maximum degree. That is to organize suicide attack units composed of Zero fighters armed with 250 kg bombs, with each plane to crash-dive into an enemy carrier.”

Our pilots will not survive anyway, wrote Onishi. “These young men with their limited training, outdated equipment and numerical inferiority, are doomed even by conventional fighting methods. It is important to a commander as it is to his men, that death not be in vain.”

Until now, Japanese leaders had refused to sanction the creation of suicide units. But after Philippine Sea and the Marianas, the hopelessness of the Japanese position caused them to relent.

In the Philippines, Onishi created the first “Special Attack Unit” to carry out formally-ordered suicide attacks against invasion shipping. On 24 October 1944, Japanese aircraft conducted the first successful kamikaze attacks of the Pacific War, sinking the American escort carrier USS St. Lo (CVE-63) and damaging six other small carriers.

A Shadow Military

It is likely that Onishi’s original intent was to employ suicide attacks only in support of the Sho Plan – the defense of the Philippines. But the sinking of the St. Lo at the cost of a single Japanese pilot seemed to validate the concept. From that point on, suicide attacks became ever-more important components of Japanese defense plans. In January 1945, Japanese Navy and Army leaders ordered all branches of the armed forces to use suicide attacks. By the middle of 1945 the Japanese had created a shadow military of special attack units equipped with specially designed kamikaze aircraft, rocket powered planes, suicide boats, human torpedoes, suicide submarines, and suicide snipers. Plans were underway to equip soldiers with hand-carried anti-tank weapons which they would place against the sides of U.S. tanks, destroying the tank and themselves, and the Japanese Army Air Force had created a special unit to train pilots to conduct suicide ramming attacks against U.S. bombers.

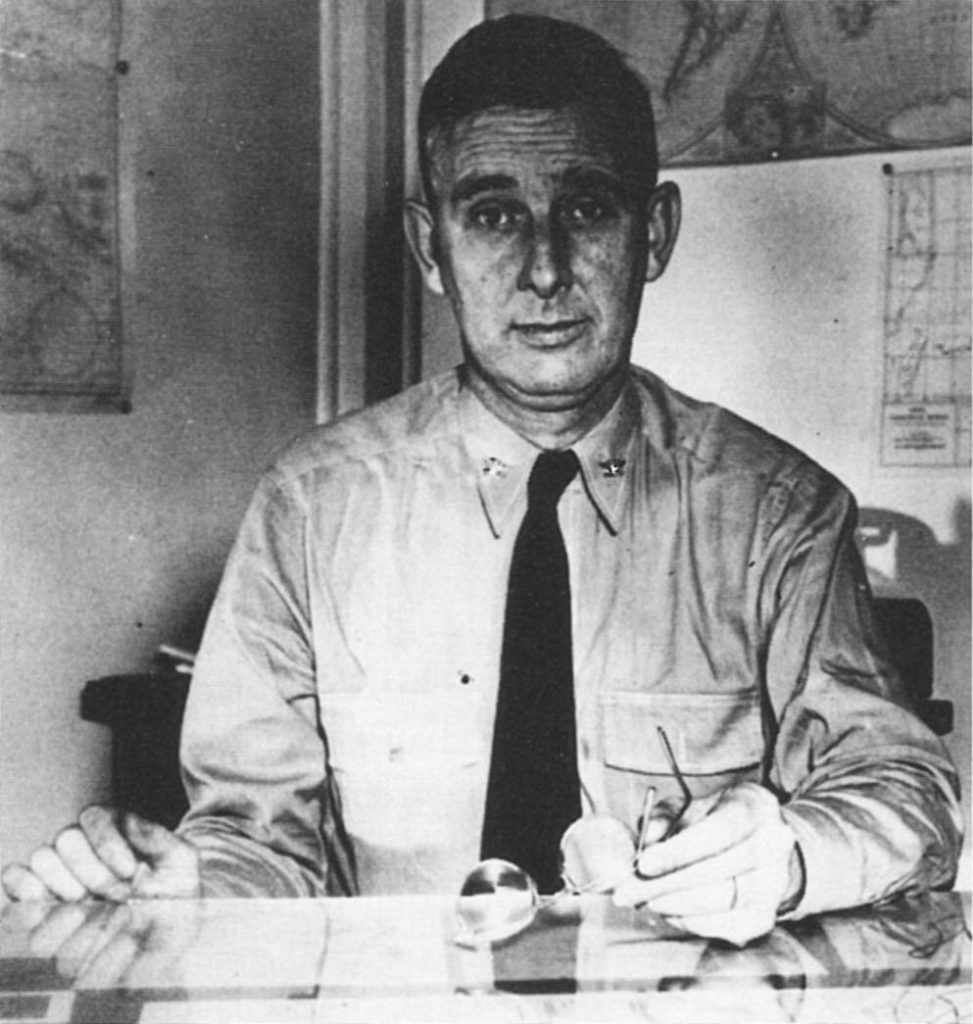

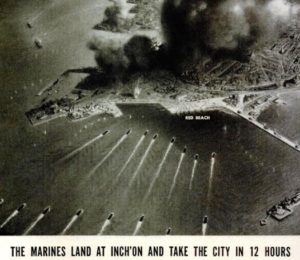

National Archives Photo 127-N-140564

While the initial Japanese kamikaze attacks against U.S. ships in the Philippines were hurriedly mounted, the suicide attacks became increasingly sophisticated as the Japanese carefully studied the results of their early missions and refined their tactics and training. Japanese military leaders recognized the enormity of the sacrifices they were asking their young pilots to make and commanders at all levels made every attempt to give kamikaze pilots the training, equipment, tactics, and support they needed to succeed in their missions and give their deaths meaning.

As the Americans advanced across the Central Pacific and through the Philippines, the creation of special attack units became Japan’s highest priority. They were believed to be Japan’s only hope for fending off the final, unthinkable catastrophe.

The Most Difficult Problem

While some U.S. planners had anticipated the use of suicide tactics, the U.S. Navy was shocked at the initial attacks. Sailors were unnerved by the realization that Japanese pilots were intentionally killing themselves in order to kill Americans.

Worse, the kamikaze attacks were significantly more effective than conventional attacks. The layered anti-aircraft defenses that had proved virtually impenetrable at the Battle of the Philippine Sea could not protect the enormous formations of warships and transports forced to operate for extended periods within range of Japanese land-based aircraft.

From October 1944 through February 1945, kamikaze attacks sank 28 U.S. ships, including two escort carriers and four destroyers, and damaged 140 more, including fleet carriers, battleships, and cruisers. Overall, the attacks killed more than 3000 U.S. sailors at a cost to the Japanese of approximately 500 planes and pilots. For the Japanese, suicide attacks were an effective and sustainable tactic.

US Navy photo

Kamikaze attacks had two main advantages over conventional attacks. First, kamikaze pilots could not be deterred by any conceivable concentration of fighter cover or anti-aircraft fire. Unless destroyed, they were committed to the attack. Second, even if heavily damaged, or if the pilot were killed during his final dive to the target, the plane – though now uncontrollable – might continue on to strike the targeted ship. U.S. after action reports bulge with accounts of kamikaze planes being shredded by anti-aircraft fire – engines aflame, wings shot off, pilots slumped over – yet continuing on to strike American ships.

Little wonder that a 1945 report from the headquarters of the U.S. Fleet called kamikazes, “by far the most difficult antiaircraft problem yet faced by the fleet.”

A Rapid Response

But though U.S. Navy commanders were surprised by the first large-scale kamikaze attacks, they were quick to respond and within weeks were identifying measures to defend against the new threat.

As soon as kamikaze tactics were identified – and the attack profiles were instantly recognizable to the astonished crews of targeted ships – the Navy began disseminating information about the new threat. Within days of the initial attacks in the Philippines, ships in the area received messages describing kamikaze tactics and suggesting possible countermeasures. Information from after-action reports, intelligence assessments, damage reports, and other sources was rapidly compiled and shared as tactical bulletins, instructions, and other forms of guidance by the new Antiaircraft Operations Research Group – established in October 1944 – and the Special Defense Section of the Pacific Fleet staff. By the end of 1944 the Navy had even produced a booklet for sailors containing the latest information on kamikaze tactics and recommended defensive measures.

By the time of the Okinawa invasion in April 1945, the Navy had developed doctrine, tactics, and procedures that blunted the effect of the massive kamikaze onslaught that the Japanese unleashed.

The Navy’s rapid response was no accident.

Throughout the Pacific War the U.S. Navy had demonstrated a remarkable ability to learn, innovate, and evolve and was quick to adopt new doctrine, organizational structures, technologies, and tactics. In contrast, the Japanese Imperial Navy never moved on from its pre-war devotion to ‘decisive battle;’ never adjusted its submarine doctrine to prioritize attacks against the U.S. Navy’s vulnerable supply lines; and never modified its aviator training programs to replace the skilled pilots lost in 1942 and 1943. Even Japan’s adoption of suicide tactics came only when they had no other option, and the change came too late to affect the outcome of the war.

By mid-1944 the U.S. Navy had greatly improved shipboard damage control, introduced Variable Timed (VT) fuses for five-inch anti-aircraft shells; increased the anti-aircraft armament of ships, created a vast logistics infrastructure to support mobile fleet operations, developed new task force formations optimized for anti-air warfare, and created combat information centers to coordinate sensor and weapons information aboard ships.

Wikimedia photo

These and other wartime innovations were possible because the interwar Navy had used reforms at the Naval War College; annual fleet problems, and the decentralization of the doctrine development process to transform itself from a traditional institution to a modern, professional organization that valued officer education, experimentation, collaborative learning, information sharing, individual initiative, and adaptability, and which actively sought insights from all levels of the service.

“The result,” wrote author Trent Hone, “was a critical mass of naval officers prepared to make decisions in rapidly changing circumstances.”

Japanese Innovation

But though the Japanese failed to rethink their overall strategy, they were quick to apply lessons learned in combat to refine their tactics and improve kamikaze performance.

As early as November 1944 the Japanese developed an intensive seven-day training course to turn novice flyers into effective kamikaze pilots. Topics covered included basic flight skills, coordination of attacks by multiple aircraft from multiple headings to overwhelm defenses, and recommended approaches to the target ship that avoided combat air patrols and minimized the volume of effective anti-aircraft fire the attackers would face.

As the war continued kamikaze attacks became more difficult to defeat as suicide pilot training was updated to reflect combat experience and Japanese Navy leaders made larger numbers of attacking planes available. The Japanese also developed tactics that reduced their chances of being detected by American radar, including flying in smaller formations to reduce radar signature, closely following returning U.S. aircraft, and frequently changing altitude and course.

A Desperate Race

Kamikaze attacks threatened to undo two-and-a-half years of U.S. Navy progress in developing effective anti-aircraft defenses. The robust defenses that worked so well at Philippine Sea struggled to cope fully with the increasingly dangerous kamikaze threat. The remainder of the Pacific War would revolve around the growing use of kamikaze attacks and the U.S. Navy’s desperate race to defeat them.

In a detailed analysis of anti-suicide efforts published in August, 1945, the Navy reported that from February through May 1945 – which included the bulk of the Okinawa campaign – Japanese suicide attacks were ten times more effective than conventional attacks. To score a hit on a U.S. ship, an average of 3.6 suicide attacks were conducted, compared to 37 conventional bombing or torpedo attacks. In addition, 27 percent of kamikaze attackers managed to hit U.S. ships, while only 2.7 percent of conventional attackers scored hits. Of course, suicide attackers suffered 100 percent attrition, as opposed to the loss of 17 percent of non-suicide planes.

But during that period, US defenses steadily improved, as the Navy made more efficient use of current equipment, devised more effective tactics, and accelerated the development and deployment of new equipment.

During the Okinawa campaign the Navy employed a highly-organized multi-layered defensive scheme against kamikaze attacks that included air attacks against kamikaze bases; aerial surveillance of Japanese bases; the use of radar picket ships and ground-based radar; enhanced combat air patrols; improvements in gunnery; more effective formations; use of speed, maneuver, and deception; and installation of new equipment.

Attacking the Source

Navy officers understood that kamikaze attacks were impossible to deter and no matter how tight the air and surface defenses were, some suicide planes were bound to leak through. To limit the number of kamikaze attackers that the fleet would have to fight off, Navy commanders ordered repeated carrier air strikes against kamikaze bases in the Philippines, Taiwan, Iwo Jima, and Japan as well as attacks against aircraft manufacturing plants. Since kamikaze pilots were not skilled enough to fly from carriers, all organized kamikaze attacks were launched from land bases and it was hoped that attacks against the sources of the raids would reduce the size and frequency of kamikaze attacks. The Navy also pressed the U.S. Army Air Force to strike kamikaze bases and aircraft manufacturing targets, and though initially reluctant, the Air Force did conduct such strikes.

While these raids destroyed more than one thousand Japanese aircraft, they did not appreciably reduce Japan’s ability to mount kamikaze attacks during the Okinawa campaign. Attacks tapered off near the end of the ground campaign only because the Japanese wanted to preserve their aircraft and pilots for the defense of the home islands. By August 1945, Japan had stockpiled more than 6,000 aircraft of virtually every description to employ as kamikazes against the anticipated U.S. invasion.

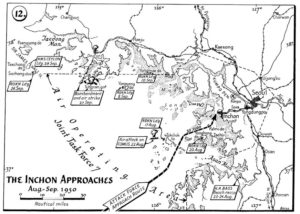

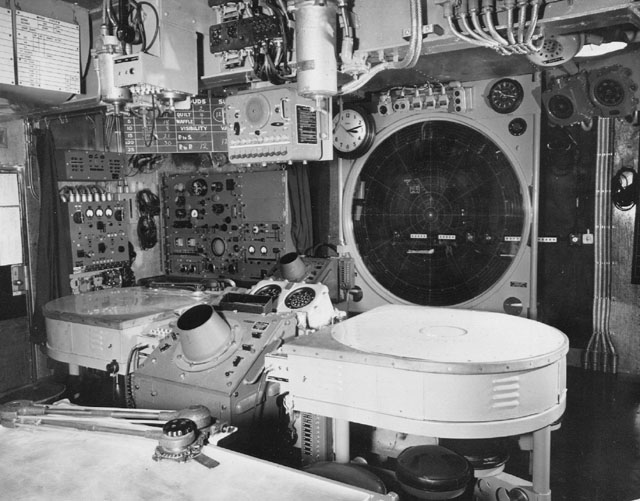

Early Warning

At the Philippines, kamikazes had often surprised American ships by approaching at low altitude from nearby landmasses, or using cloud cover to hide their approach. Some ships were struck before they were able to fire at their attackers. In planning for the invasion of Okinawa, where they knew the Japanese would conduct large-scale kamikaze attacks, U.S. leaders established a ring of fifteen radar picket stations 40 to 60 miles from the invasion fleet operating areas to give the fleet advance warning of Japanese air attacks from Kyushu and Taiwan. Since most U.S. combat ships by then were equipped with air search radar that could detect planes from 75 to 100 miles away, the use of radar picket stations extended the fleet’s radar coverage out to 150 miles.

Initially, each station was manned by a radar-equipped destroyer with a fighter direction team embarked, but after several weeks of concentrated Japanese kamikaze attacks against the exposed ships, the Navy began to assign landing craft, patrol boats, and sometimes a second destroyer or destroyer escort to the stations to provided additional antiaircraft capability. Eventually each station was also protected by a Combat Air Patrol of up to 12 Navy fighters, reassigned from CAPs protecting the fleet carriers.

Still, the radar picket ships – operating far from the robust defenses of the fleet – suffered greatly. Of the 206 U.S. ships that served as radar pickets, 60 were damaged or sunk by kamikazes.

US Navy photo

As soon as possible, radar stations were established on islands around Okinawa which allowed some of the floating stations to be abandoned, but the stations at longer ranges from Okinawa remained in operation through the end of the campaign.

But though the cost was terribly high, the picket ships were effective, as they extended U.S. defenses, greatly reduced the number of surprise attacks, vectored fighter aircraft to meet incoming raids, shot down many Japanese planes, ensured that no enemy planes were trailing returning U.S. aircraft, and rescued downed American airmen.

Navy planners found the pickets so useful that they developed plans for increased use of ships in that role during the anticipated invasion of Japan. New destroyers were modified by removal of their torpedo tubes and the installation of large height-finding radars and additional anti-aircraft guns. The Navy even equipped some submarines for use in the radar picket role, though the boats that were provided with advanced radars never actually performed the function.

But though the radar pickets were largely successful, they were not a solution to the kamikaze problem. Despite the best efforts of the radar picket ship crews in appalling circumstances, a large fraction of attackers made it through to the invasion fleet. Radar was at that time a new and immature technology, and equipment failures, operator inexperience, and the Japanese use of aluminum strips to jam U.S. radar reduced its effectiveness.

Combat Air Patrol

In addition to detecting incoming raids, radar picket ships directed Combat Air Patrol (CAP) fighters to intercept positions. The Navy hoped to intercept the raids as far from the fleet as possible to give American pilots sufficient time to break up attacks while staying out of the range of shipboard anti-aircraft fire.

The combination of early warning, fighter direction, air discipline, and robust Combat Air Patrols enabled U.S. fighters to drive off or shoot down nearly half of all kamikaze attackers before they reached the U.S. invasion fleet at Okinawa, including more than 60 percent of planes approaching the American fast carrier task force.

The Navy’s Grumman F6F Hellcats and Vought F4U Corsairs were technologically superior to Japanese planes – including the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter that had been so successful at the beginning of the war. Japanese aircraft not only lacked sufficient armor, self-sealing fuel tanks, and adequate armament, but U.S. pilots were vastly more skilled. By 1945 nearly all of the most experienced Japanese pilots had been killed and had been replaced by novices.

US Navy photo

As Japanese commanders were aware that air-to-air combat would decimate their attacks, Japanese kamikaze pilots and their escorting fighters were instructed to avoid U.S. aircraft whenever possible. When intercepted by CAP fighters, Japanese raids would disperse with a few escorting fighters engaging the CAP aircraft while most of the Japanese planes attempted to evade by diving to very low altitude or scrambling for nearby clouds.

If CAP fighters broke up the Japanese raid more than fifty miles from the fleet, very few Japanese planes would survive to find and attack U.S. ships. If the intercept occurred within 25 miles of the fleet, most of the scattered Japanese planes would reach U.S. ships.

Air interception of incoming raids proved so effective that Navy commanders continually changed the composition of carrier air groups to include more fighters and fewer bombers, though this inevitably reduced the striking power of the fleet.

Gunnery

Japanese aircraft that evaded CAP fighters and managed to find American ships faced a final obstacle: the massed antiaircraft fire of the targeted ships themselves.

Throughout the war the U.S. Navy had continually improved antiaircraft doctrine, armament, and gunfire accuracy aboard surface ships. By 1945, fleet carriers averaged 136 separate guns of various calibers, while heavy cruisers averaged 83 guns and destroyers 42.

Antiaircraft defenses had to be effective at long range for times when Japanese planes were detected early, and also at very short ranges, during the final moments of the kamikaze attack. By the time of large-scale kamikaze raids, the primary long-range antiaircraft weapon was the 5 inch/38 caliber dual purpose gun firing VT “variable time” shells incorporating tiny radar proximity fuses, while the primary machine guns were the 40 millimeter and 20-millimeter automatic cannons. Five-inch guns and 40-millimeter guns could be radar-controlled while 20-millimeter guns were equipped with gyroscopically-stabilized gunsights.

US Navy photo

While gunners constantly trained to improve accuracy, the Navy looked for ways to speed up antiaircraft fire response and better coordinate and control the antiaircraft fire of individual ships and formations. The Combat Information Center – first developed in 1942 but continually refined and improved – was critical in providing officers with a clear tactical picture of the confusing and fast-changing air battle. CICs received, coordinated, analyzed, and displayed threat information from radars, radio reports, lookouts, and any other source.

Despite early warning systems and robust Combat Air Patrols around Okinawa, Japanese kamikazes still managed to appear suddenly in the skies above U.S. ships. When that happened, a ship’s survival might depend on how fast its gunners could fill the air with projectiles. Ships responded by opening fire as soon as possible without waiting for perfect firing solutions; using all available directors, including manually-operated directors for five-inch guns; releasing 40 mm and 20 mm guns to sector control; sending up a large volume of fire; and maintaining the maximum rate of fire for as long as possible.

Formations

Since the carrier versus carrier battles of 1942, the U.S. Navy had abandoned single carrier formations and instead formed task forces around multiple carriers. The great battles of Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf in 1944 demonstrated the value of two or more carriers operating together protected by one or more screens of escorting ships. By late 1944, U.S. antiaircraft doctrine stipulated that screening vessels should be stationed between 1500 and 2000 yards away from ships being screened and from other escorting ships. This distance massed antiaircraft fire while allowing individual ships room to maneuver if attacked.

But as Japanese mass kamikaze attacks increasingly threatened task force ships, Navy commanders tightened their formations and looked for other ways to strengthen defenses.

At Okinawa, Navy officers recognized that the best defense against kamikazes was the closest possible formation with a single circle of escorting vessels spaced 1000 yards apart. Some officers recommended even-tighter screens, with escort vessels closing to within 200 yards of screened ships when attacks were imminent. But tighter screens increased the chance of hitting friendly ships when firing at low-level attackers, so Navy commanders stressed the need for antiaircraft fire coordination plans, fire discipline and rigorous training for gun crews.

US Navy photo

To maximize the effectiveness of formation antiaircraft defense, task force CIC’s delegated specific defensive tasks like fighter direction or air search to individual ships or groups of ships while serving as the primary CIC for the entire formation.

Speed and Maneuver

High speed evasive maneuvers were universally employed by ships targeted by kamikazes. While piloting a plane to the moment of impact against a maneuvering ship was easier than striking a ship with a bomb or torpedo, it was still no easy task. Kamikaze pilots were mostly novice flyers, and their attack profiles – which culminated in high-speed dives – were difficult to master.

U.S. ships were instructed to go to full speed as soon as attackers appeared, making repeated tight turns and opening antiaircraft fire at maximum range. When kamikaze planes began their final attack run, destroyers and other small ships were directed to maneuver to bring their gunnery directors and the maximum number of guns to bear. This generally meant that ships would turn to present their beam to high-diving attackers, which had the added benefit of increasing the chance that a diving kamikaze would miss the ship. Ships facing low-level kamikaze attacks were instructed to turn away from their attackers to present as narrow a target as possible and protect the ship’s control station on the bridge.

Two problems with high-speed maneuvering, at least on smaller ships, were that it sometimes caused fire control radars to lose the target and it disrupted the aim of shipboard gunners. But when facing a diving enemy intent on crashing a bomb-laden aircraft into his ship, few captains could refrain from ordering up the most radical evasive maneuvers possible.

Deception

As the toll from kamikaze attacks grew, U.S. Navy commanders looked for any additional steps they could take to reduce the threat. That’s how the high-speed transport USS Barry (APD-29) finished its days as a kamikaze decoy.

A World War I era destroyer later converted to a transport, Barry was hit by a kamikaze and heavily damaged in May, 1945. With a wooden patch on her hull; all useful equipment removed; and lights and smoke pots rigged to simulate antiaircraft fire, funnel smoke, and battle damage, Barry was towed by a fleet tug to a position where it was hoped she would attract kamikaze planes, distracting them from more worthwhile targets.

A National Archives and Records Administration. photo from “Fire from The Sky” by Robert C. Stern.

Unfortunately, the ruse worked better than anticipated, and the unmanned Barry and an escorting LSM were both struck by kamikazes almost immediately. Two sailors on the LSM were killed and both ships sank.

More conventionally, U.S. amphibious ships and transports concealed themselves with smokescreens while escorting ships hid themselves in cloud shadows, rain squalls, and against the dark side of land masses.

Task Force 69

In July 1945, still reeling from the mass kamikaze assaults during the Okinawa campaign and expecting even larger and more sustained attacks during the planned invasion of Japan, Navy leaders established a special task force to develop more effective countermeasures against kamikaze attacks.

Led by Vice-Admiral Willis A. ‘Ching’ Lee, Task Force 69 was directed to test tactics, equipment, ammunition, and other elements of anti-kamikaze defense with an emphasis on improving early detection and tracking, increasing the effectiveness of antiaircraft fire, and evaluating new weapons and procedures. The task force was allotted a former battleship – converted to a trials ship – two cruisers, two destroyers, two destroyer escorts, four auxiliary ships, and two squadrons of aircraft.

The task force issued no report before the end of the war in August 1945, but was renamed the Operational Development Force in September 1945 and continued its work. The organization later evolved into the Navy’s Test and Operational Development Force (OPTEVFOR).

A Higher State of Preparedness

Kamikaze attacks during the final ten months of the Pacific War sank 66 allied ships, damaged more than 250 others, and killed more than 6,000 U.S. sailors.

Yet, the U.S. Navy’s commitment to collaborative learning, experimentation, sharing information, individual initiative and adaptability coupled with the unsurpassed courage and dedication of tens of thousands of sailors enabled the service to blunt the impact of suicide attacks.

In a postwar history of the Navy, Captain Edward L, Beach wrote that “ships in the attack zone kept themselves in a higher state of preparedness against air threat than any warships had ever done the world over.”

October 14, 2021

A version of this story was posted on the Military History Now website: https://militaryhistorynow.com/2021/10/12/the-kamikaze-war-inside-the-u-s-navys-race-to-defeat-japans-suicide-pilots/

Sources:

Beach, Edward L., CAPT, USN, (Ret); The United States Navy: 200 Years; Henry Holt and Company; New York; 1986.

Benedict, Ruth; The Chrysanthemum and the Sword; Patterns of Japanese Culture; Houghton Miffin Company; New York; 1946,.

Evans, David C., editor; The Japanese Navy in World War II; second edition; Naval Institute Press; Annapolis, MD; 1989.

Hone, Trent; Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898-1945; Naval Institute Press; Annapolis, MD; 2018.

O’Neill, Richard; Suicide Squads of World War II; Hippocrene Books; New York; 1989.

Smith, Peter C.; Kamikaze: To Die for the Emperor; Pen & Sword Books; South Yorkshire, UK; 2014.

Stern, Robert C.; Fire from the Sky: Surviving the Kamikaze Threat; Seaforth Publishing; Barnsley, Great Britain; 2010.

Stewart, Adrian; Kamikaze Japan’s Last Bid for Victory; Pen and Sword Books; Yorkshire, UK; 2020.

Timenes, Nicolai; Analytical History Of Kamikaze Attacks Against Ships Of The United States Navy During World War II; Center for Naval Analysis; November 1970.

Toll, Ian W.; The Conquering Tide, Volume Two of the Pacific War Trilogy; W. W. Norton and Company, New York, 2015.

United States Navy Department; Anti-Suicide Action Summary; August 1945; http://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/a/anti-suicide-action-summary.html Retrieved 7.5.2015.

Woodford, Shawn R. Ph.D., Historian, NHHC Histories and Archives Division; The Most Difficult Antiaircraft Problem Yet Faced by the Fleet; Naval History and Heritage Command website; June 2020; The Most Difficult Antiaircraft Problem Yet Faced By the Fleet (navy.mil) ; Retrieved 8.4.2021