Unchecked urban sprawl is weakening Greater Cleveland, causing disinvestment and abandonment of inner-city neighborhoods and threatening the character of rural communities in the surrounding counties, said a panel of local government officials Wednesday.

“Greater Cleveland’s population stopped growing in 1970,” said Northern Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA) Chief Executive Grace Gallucci. “But we have continued to develop formerly open land, build new infrastructure, and expand the footprint of our community with dire consequences for environmental sustainability, economic efficiency, and racial equity.”

Gallucci spoke as a panelist on a Cleveland City Club virtual forum titled “Sprawl Versus Smart Growth: Building an Equitable and Thriving Region.” Joining Gallucci on the panel were Maple Heights Mayor Annette Blackwell and Solon Mayor Eddy Krause.

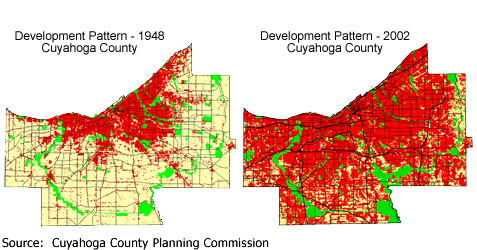

Since 1970, when the population of the five-county Greater Cleveland metropolitan area peaked at 2.3 million, the region’s population has declined by more than 5 percent. But during the same period the amount of developed land has increased by 20 percent. As a result, fewer Greater Clevelanders are now paying to build and maintain significantly more neighborhoods, roads, bridges, schools, commercial buildings, fire stations, and other costly services. A less efficient use of dwindling resources could scarcely be imagined.

Worse, unchecked sprawl is inexorably hollowing out the core of the urban area, causing large-scale disinvestment and abandonment and contributing to higher levels of poverty, crime, racial segregation, and economic inequality. In a region with no population growth, every house or business constructed on undeveloped land on the region’s periphery means one more vacant housing unit or commercial building in the center of the city.

None of this is news, of course.

Greater Cleveland has been expanding outward for more than one hundred years. The first ‘streetcar suburbs’ in Cuyahoga County – East Cleveland, Cleveland Heights, and Lakewood – were developed in the first two decades of the twentieth century in areas immediately adjacent to the City of Cleveland. Through the 1920’s, a second ring of transit-dependent suburbs formed, including Maple Heights, Rocky River, Garfield Heights, Shaker Heights, and Euclid. Today we refer to these communities as ‘inner ring suburbs,’ and they are struggling with declining population, job losses, and increasing poverty as economic growth moves farther away from the central city.

During the 1930’s and 1940’s, the depression and World War II slowed growth in suburban areas, but once the war was over the combination of pent-up demand for new housing and federal transportation and housing policies led to the rapid development of a ring of auto-centric suburbs beyond the earlier suburbs, including Parma, Bay Village, Lyndhurst, and Fairview Park. Growth of these suburbs was widely celebrated, and the steady flow of job-seekers into the region maintained population growth.

By the 1960’s though, Greater Cleveland and other urban areas across the Great Lakes region saw their economies savaged by massive losses of manufacturing jobs which led to a reduction of in-migration and an end to decades of population growth. Yet construction of new homes and businesses continued in an outer ring of suburbs, including Westlake, Solon, Strongsville, North Royalton, North Olmsted, and Brecksville. Today, development has shifted into surrounding counties, where it continues. The result is that our region is now comprised of a declining core of poor – and getting poorer – communities surrounded by a ring of threatened suburbs surrounded by a ring of stable communities surrounded by a final ring of ongoing development.

While sprawl has been historically driven by the desire of residents and businesses to move away from the urban core for open space, larger homes, less expensive land; to escape pollution, crime, and poverty; and to avoid racial integration; government policies have played an outsized role.

As late as the 1960’s, said Gallucci, regional planners believed that Greater Cleveland’s population – which had been growing steadily for 150 years – would continue to grow and the region would gain a million new residents by 2010. Highway projects and other forms of public infrastructure were designed to accommodate this larger population. But the unexpected loss of manufacturing jobs reduced in-migration to the region and halted population growth. Yet the drivers of sprawl remained in place.

As a result, sprawl has continued to bleed residents, jobs, and money from Cleveland and its inner ring suburbs and transfer entire neighborhoods and associated economic activity to outer suburbs and surrounding counties, even as the devastating consequences are well-understood.

“Continuing our pattern of ever-expanding sprawl will increase disinvestment and abandonment in neighborhoods in the center of the region,” said Gallucci, “exacerbating racial and economic segregation and inequality – making all of our problems worse and undercutting our efforts to redevelop the city.”

The distressing reality is that with a stagnant population, every new home or commercial building constructed in the outer reaches of Greater Cleveland means an abandoned home or structure in the urban core and a corresponding loss of economic activity and tax revenues.

Growth in one part of the region should not result in disinvestment in other parts, Gallucci said. What we need is smart growth. Rather than continually developing open land on the region’s periphery, we should find ways to encourage redevelopment in areas where infrastructure already exists.

But that has been a message that communities on the periphery of the region have been happy to ignore. Instead, suburbs across Greater Cleveland have engaged in decades of self-defeating efforts to poach businesses and residents from each other – fighting over economic scraps rather than working together as fellow members of an integrated economic unit that is facing serious challenges from other regions throughout the nation and the world.

It is past time for that region-wide infighting to stop, said Solon mayor Eddy Krause. Located on Cuyahoga County’s southeastern edge, Solon has emerged as one of the big winners in the sprawl sweepstakes. The city is now home to the second largest concentration of jobs in the region, trailing only downtown Cleveland. But Krause realizes that his suburb’s continued success depends on finding a way to share Solon’s good fortune with the city and its inner ring suburbs.

“Our competition isn’t each other,” he said. “Our competition is Dublin, Ohio; Indianapolis; Pittsburgh; Austin, Texas.”

Greater Cleveland communities need to work together, he said.

That’s an attitude that Maple Heights mayor Annette Blackwell welcomes. Her city has been sledgehammered by sprawl-induced disinvestment. Once a tidy middle-class suburb, Maple Heights has suffered enormously from the closure of local businesses, declining population, dwindling property values and rising poverty.

Blackwell agrees that cities across the region need to work together, and she believes it is happening more and more. “But that wasn’t always the case,” she pointed out. “I didn’t feel that way six years ago. There is still work to do.”

Sprawl is not just a threat to areas in the urban core, said Gallucci. Rural communities on the outskirts of the region and farmers have expressed concern that development will destroy productive agricultural land, reduce wildlife habitat, cause flooding, and permanently alter the character of smaller communities.

“We have to do better,” said Blackwell. “We are forced to do better.”

February 6, 2021

Photo credit: Angie Schmitt, Streetsblog USA

See also:

https://www.cleveland.com/architecture/2014/04/smart_growth_america_report_gi.html