We know the story. Part of it, anyways.

It was 1957, three years after the United States Supreme Court ruled that ‘separate but equal’ public schools were inherently unequal. The court’s Brown versus Board of Education decision meant that America’s public-school systems had to stop segregating schools by race.

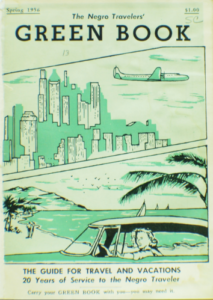

Racially segregated schools were a cornerstone of the brutal Jim Crow system of government-sanctioned discrimination and segregation that was disfiguring America’s southern states. Racial discrimination was rife in the rest of the country, too, but outside the south it lacked the full-throated support of state and local government.

Opposition to school desegregation was widespread throughout the south. Segregationists – a euphemistic term for virulent racists – bitterly opposed any attempts to put black and white children in the same classroom. But the law was the law, and many school districts were making at least token efforts to comply.

The Little Rock, Arkansas school district was one such district. Though their half-hearted desegregation plan was designed to delay the process as long as possible and to severely limit the number of black children who would actually sit in class with white children, it did allow for a handful of black students to attend Little Rock’s Central High School in the fall of 1957.

So, on the evening of September 3, 1957, after three years of resistance and delay, nine black teenagers, handpicked by the Board of Education, freshly scrubbed and almost comically naive about the reception that awaited them, readied themselves to enter Little Rock’s Central High School for their first day of classes. Later, they would become known as the Little Rock Nine, but as they waited anxiously that night, they were simply nine nervous students. They were Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Melba Patillo, Minniejean Brown, Thelma Mothershed, Gloria Ray, Carlotta Walls, Terrence Roberts, and Jefferson Thomas.

The Little Rock Nine

Minniejean Brown, then sixteen, recalled their anticipation during an interview years later. “The nine of us were not especially political,” said Brown. “We thought, we can walk to Central, it’s a huge, beautiful school, this is gonna be great.”

It wasn’t great.

The black students’ first attempt at entering the school was turned back by a jeering mob of hundreds of white supremacists and nearly 300 hostile Arkansas National Guardsmen. The Guardsmen had been posted to the school by Arkansas governor Orval Faubus not to protect the black students from the mob, although opposition to desegregation of the high school had been building for weeks, but to physically prevent the students from entering the building. A week later, with the Guardsmen replaced by city and state police, a second attempt was thwarted when a larger mob of more than 1,000 howling racists, many armed, broke through police lines and threatened to drag the students out of the building, after the nine students had been spirited in through a side door.

That fiasco prompted President Dwight D. Eisenhower to send 1,000 highly-disciplined paratroopers of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock to enforce the federal court order that Little Rock’s schools must be desegregated.

Thus, as history records, on September 25, 1957, escorted by U.S. Army soldiers, the nine black students attended classes at Central High School for the first time. In many accounts, that’s the end of the story. A federal court ordered desegregation. Segregationists defied the court’s orders. Eisenhower sent federal troops. Black students went to school. Crisis averted. High-fives all around.

U.S. Army soldiers lead black students into Central High School. (US Army photo)

Except that wasn’t the end of the story. For the nine black students, it was just the beginning. What followed was eight months of unceasing harassment, threats, verbal abuse and physical attacks by white students in a vicious campaign that was coordinated by their parents and other adults and was tolerated – and in some cases encouraged – by school officials.

Despite soldiers stationed inside the school – 101st Airborne paratroopers for two months, then federalized National Guardsmen for the remainder of the school year – the black students faced daily assaults and harassment. They were continually tripped, kicked, slapped, shoved, insulted, and threatened by white students. Flaming wads of paper were tossed on the black girls. Melba Patillo had acid thrown in her face and only quick action by her soldier escort saved her eyesight. Elizabeth Eckford was stabbed by sharpened pencils. Minniejean Brown had food dumped on her in the cafeteria at least three times.

Soldier escorts were forbidden to touch harassing students and school officials refused to take action unless an assault occurred within their immediate view. The most aggressive students quickly realized that they could terrorize the black students with impunity. While some teachers stopped verbal and physical assaults in class, others did not.

It was a terrifying experience that shocked the nine students, even though they had been warned that there would be opposition. “I figured, I’m a nice person. Once they get to know me, they’ll see I’m okay. We’ll be friends,” said Brown.

In fact, the campaign of intimidation had begun months before the school year started. In 1956, aware that the school board was creating a plan for integration, Little Rock residents formed the Capital Citizens Council (CCC), a local offshoot of the White Citizens Council that was resisting desegregation in Mississippi. The CCC launched an anti-integration media campaign, organized rallies, and tried to pressure the school board to drop the desegregation plan. CCC statements charged that the NAACP, which supported integration, was an agent of international communism, as if only communists might want their children to receive a decent education. In August, 1957, less than a month before school was to begin, Little Rock segregationists formed the Central High Mother’s League in an attempt to present a less-threatening image than the CCC and its White Citizen’s Council model. In truth, fewer than 25 percent of Women’s League members were actually the mothers of Central High students, but all of the group’s members were adamantly opposed to desegregation of the public schools. The Mother’s League filed anti-integration lawsuits, pressured pubic officials, held public rallies, and organized a school walkout.

As the reality of court-ordered desegregation grew nearer and as public opposition increased, Arkansas governor Orval Faubus saw an opportunity to resurrect his fading political career. Until then considered a moderate Southern politician on race – though moderate is a relative term, as he was in no way an advocate of anything remotely resembling social, political, or economic equality for blacks – Faubus quickly assumed a leading role in opposition to school desegregation. His actions would prompt federal intervention and would prolong the crisis for many months, damaging the city’s reputation and leading to the closure of all Little Rock high schools for a year, but in the end, it would also result in his re-election to a record six terms as Arkansas governor.

In the weeks before the new school year was to start, segregationists targeted the families of the black students who were planning to attend Central High School. Families received threatening phone calls and visits at their homes from members of the Capital Citizen’s Council hinting darkly of trouble if their children attempted to enter Central. Other calls were made to black community leaders, to encourage them to dissuade any black children from attending Central, warning of dire consequences for the entire black community if desegregation succeeded. While more than 500 black students lived in Central High’s attendance area, just eighty expressed a desire to attend the school. After interviewing all of the volunteers, the school board selected 17 to be the first group to integrate the school. But when they were told that they would not be able to participate in any extracurricular activities, and their parents were threatened with loss of their jobs, eight of the 17 elected to remain at the local black high school, leaving nine to be the first blacks in a school with nearly 2,000 white students.

None of the nine black students saw themselves as pioneers at the start of their ordeal. They had volunteered to go to Central for the same reasons white students might have volunteered: it was close to home, it was well-equipped, it had a sterling reputation. They only wanted a chance for a better education. None of the nine had any special desire to attend school with white students. Having lived all their lives in the oppressive atmosphere of the segregated south, they knew virtually nothing about white people. “I really thought that if we went to school together, the white kids are going to be like me, curious and thoughtful, and we can just cut all this segregation stuff out,” Brown recalled.

At the time, Central High School was the most prestigious high school in Arkansas. In addition to local funding, the school received $1.5 million each year from the state to maintain programs. Meanwhile, Horace Mann – the nearby high school that had been built for black students – received no state funding. Its programs were paid for by donations. Horace Mann was actually a good school, with an outstanding faculty and a fine reputation. The school was a source of pride in Little Rock’s black community. But the black high school offered fewer classes than Central, had fewer activities, had less laboratory equipment, and relied on the white school’s hand-me-downs for textbooks, equipment, and athletic uniforms. Of course, this was the pattern throughout the south, and in much of the north as well, and it was one of the reasons that the Supreme Court had ruled that separate was not equal.

Each of the nine black students had been selected based on a careful review of their academic record, their temperament, and an interview with the school superintendent. They all came from stable, middle class families. Their parents were professionals – teachers, preachers, nurses, business owners. The students themselves were studious and well-mannered, regular churchgoers who planned to go to college. Most of all, they were unlikely to lash out violently at harassment or abuse.

And for the most part, they didn’t.

For the first two months of the school year, the 101st Airborne remained in Little Rock. Soldiers were stationed in the school and each black student was assigned an escort. While the presence of troops deterred some violence against the blacks, bolder, more committed segregationists soon recognized that troops would not protect the black students from verbal and physical harassment.

U.S. Army soldiers escort nine black students to Central High School. (US Army photo)

As a result, threats, assaults and harassment against the nine started immediately and slowly increased as community anger at the dispatch of federal troops rose. Eisenhower himself wanted the paratroopers withdrawn as soon as possible, and school and military officials quickly began reducing the visibility and numbers of soldiers in the building.

For the beleaguered nine, each reduction in troops meant an increase in harassment and attacks. At Thanksgiving, the 101st was withdrawn completely, and the disciplined paratroopers were replaced with barely trained and mostly indifferent Arkansas National Guardsmen. Attacks against the nine quickly spiked.

Not all of the white students participated in the campaign of harassment and assaults. It is likely that no more than 200 white students actually carried out attacks. A few white students made friendly gestures, but most had been intimidated by hardcore segregationist warnings not to show any kindness to the nine black students.

Week after week, the nine black students faced the abuse and hostility of hundreds of openly racist students and the cold indifference of many hundreds more. Teachers and administrators who could have controlled the offenders looked the other way. Segregationists interpreted each reduction in security as a victory, and a dizzying pattern emerged: as security measures were slowly reduced, attacks against the nine correspondingly rose. In February, Minniejean Brown was expelled after several confrontations with white students, all of which were started by whites. This “victory” further incited the segregationist fringe, as they taunted the others with the chant, “One down, eight to go.”

Yet the remaining eight soldiered on. Whatever hopes or dreams they had once entertained about being accepted had been long forgotten. Now, they were warriors. They fought back – not with kicks or pushes or hate-filled rants – but with courage and a steely determination to prevail. They drew strength from their families and their community as they now fully recognized the importance of what they were doing.

But the price they paid was harrowing. Their families were constantly harassed. Each night, their phones rang with threatening calls and all-too-often rocks were thrown through their windows. The police were no help. After decades of brutality at the hands of law enforcement, southern blacks knew never to call on police for assistance. At least two of the parents were fired from their jobs because of their children’s involvement in desegregation and at least one parent had to leave town to find work as a brick mason. As desegregation continued, some whites took out their frustrations on other blacks, and some in the black community blamed the nine and their families for the loss of their jobs and the loss of social services that they had relied on.

Eventually, the year came to an end. Though many traditional senior activities were cancelled because of the continued threat of violence, a graduation ceremony was held, and Ernest Green, one of the nine, became the first black graduate of Central High School.

But even the end of the school year wasn’t the end of the story. Lawsuits hoping to halt the desegregation effort continued through the summer and into the next year. When the courts refused to halt desegregation, Governor Faubus closed all three public high schools in the city. The schools remained closed for the entire 1958-1959 academic year. In September 1958, a special election was held in Little Rock asking voters if integration should continue. Voters overwhelmingly opposed integration, 129,470 against, 7,561 for.

With all public high schools closed, more than 3,600 students were left to find their own education. More than 750 white students enrolled at a newly established private school. Many other students left town to live with relatives or friends to continue their eduction. Because of the unrelenting stream of death threats against the Nine, the NAACP arranged for several of the students to find temporary homes in other cities.

When public schools reopened for the 1959-1960 school year, only two of the Little Rock Nine returned to Central High School. The rest had graduated from other schools or had moved away. In the end, all of the Nine left the south, and though all were scarred by their experiences, all went on to successful careers.

Little Rock’s public schools were not fully integrated until 1972.

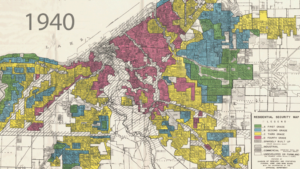

Today, the results of the Brown decision are mixed. The outrageous resource disparity between black and white schools has been largely eliminated and black academic performance has greatly improved. But white performance has also improved, so a large racial achievement gap remains. Meanwhile, white flight and segregationist housing policies have reversed early gains in school integration.

October 24, 2020

“Somewhere along the line, [staying at Central High] became an obligation. I realized that what we were doing was not for ourselves”

–Elizabeth Eckford, one of the “Little Rock Nine”

“Black folks aren’t born expecting segregation, prepared from day one to follow its confining rules. Nobody presents you with a handbook when you’re teething and says, ‘Here’s how you must behave as a second-class citizen.’ Instead, the humiliating expectations and traditions of segregation creep over you, slowly stealing a teaspoonful of your self-esteem each day.”

– Melba Patillo Beals, Warriors Don’t Cry, Simon Pulse, New York, 1995.

Sources:

Beals, Melba Patillo; Warriors Don’t Cry, Washington Square Press; New York, 1994.

Beals, Melba Patillo; I Will Not Fear; Revell; Grand Rapids, MI; 2018.

Breen, Daniel; Elizabeth Eckford Recounts “Hell” of Little Rock Central High School Desegregation; UALPublicRadio.org; January 30, 2020; https://www.ualrpublicradio.org/post/elizabeth-eckford-recounts-hell-little-rock-central-high-school-desegregation Retrieved 5.27.2020.

Chafe, William H.; Gavins, Raymond; Korstad, Robert, editors; Remembering Jim Crow; The New Press; New Yprk; 2001.

Harvey, Lucy; A Member of the Little Rock Nine Discusses Her Struggle to Attend Central High; Smithsonianmag.com; April 22, 2016; https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/member-little-rock-nine-discusses-her-struggle-attend-central-high-180958870/ Retrieved 5.27.2020

Honey, Michael K.; Little Rock at Fifty; HistoryNet.com; originally published in the October 2007 issue of American History; https://www.historynet.com/little-rock-50.htm Retrieved 5.27.2020.

Margolick, David; Through a Lens Darkly; VanityFair.com; https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2007/09/littlerock200709 Retrieved 5.27.2020.

Williams, Juan; Eyes on the Prize; Penguin Books; New York; 1987.

Choices People Made: The Little Rock Nine and Their Parents; Facing History website; https://www.facinghistory.org/for-educators/educator-resources/resource-collections/choosing-to-participate/choices-people-made-little-rock-nine-and-their-parents Retrieved 5.27.2020.

History of Little Rock Public Schools Desegregation: Internet Archive; https://web.archive.org/web/20061217140900/http://www.centralhigh57.org/1957-58.htm Retrieved 5.27.2020.

‘They Were Hanging Effigies,’ Little Rock Nine Activist Recalls Hate Campaign to Block Desegregation; RT.com; https://www.rt.com/usa/404300-little-rock-nine-anniversary/ Retrieved 5.27.2020.