It was the grandest of grand openings, but it wasn’t the beginning of an era, it was the end.

On June 28, 1930, 2,500 of Cleveland’s most prominent citizens gathered to celebrate the opening of the city’s massive Union Terminal complex. Centered on the two-level Union Terminal Station and crowned by the 52-story Terminal Tower, the complex was the largest mixed-use, multi-building development in the United States. New York’s Rockefeller Center – similar in concept but greater in execution – wouldn’t be completed until later in the decade.

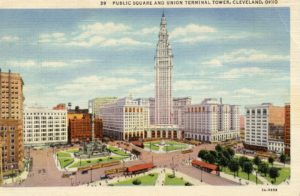

Vintage postcard of Cleveland’s Terminal Tower and Union Terminal complex

The grand opening was the culmination of more than twenty years of effort by the railroad-owning Van Sweringen brothers, who hoped to replace Cleveland’s five separate railway stations with a single, lavish terminal. As planning progressed, their vision expanded, and they ultimately proposed a project that would reshape the face of the city. The six gleaming buildings that comprised the complex, with a seventh under construction and an eighth planned, confirmed Cleveland’s position as one of the most prosperous cities in America.

Today, as Cleveland struggles with all of the ills associated with declining manufacturing, racial discord, public corruption, and intractable poverty, it is hard to recall just how esteemed the city was in the early decades of the twentieth century.

Author Lincoln Steffins famously called Cleveland “the best-governed city in the United States.” And, for a time, the city was well-governed. City schools, the police department, the public library, and many civic and cultural institutions were nationally respected. Elliott Ness had been the safety director, John D. Rockefeller started Standard Oil in the city, and Cleveland industrialist Mark Hanna had obtained the presidency for his protégé, William McKinley.

From the time of the Civil War, transportation links, industry, and immigration fueled Cleveland’s ascent as a manufacturing powerhouse. The city’s combination of steel-making, auto manufacturing, metal casting, and paint production provided jobs and profits. From 1900 to 1910, the city’s population grew from 381,000 to 560,000. By 1930, as revelers gathered to celebrate the opening of the Union Terminal complex, the city’s population had reached 900,000, making Cleveland the sixth largest city in America and the third largest metropolitan area, trailing only New York and Chicago.

The Union Terminal complex was a gargantuan, mixed-use, multi-modal transportation hub, built before anyone knew what multi-modal meant. The complex accommodated long-distance passenger trains, interurban trains, rapid transit trains, taxis, buses, and private automobiles. The project replaced 35 acres of mostly deteriorating structures, displacing 15,000 residents and countless businesses.

At its opening, the complex included six interconnected buildings: the station, a hotel, and four office buildings, including the Terminal Tower, which would remain the tallest building outside New York City until 1967. A department store was under construction and a massive post office was planned. It was a city-within-a-city, where more than 10,000 people worked and many thousands more passed through each day.

The project itself embodied many of the elements that made Cleveland great. Immigrants fueled the city’s industrial rise, and thousands of immigrant laborers worked on the Terminal complex. Excellent transportation links via the lake, the Ohio Canal, and numerous railroads made Cleveland a great commercial center, and the Union Terminal complex was at heart a transportation nexus. As the city itself was originally founded as a real estate venture, the Union Terminal was also intended originally to support the Van Sweringen’s property enterprise in Shaker Heights by linking the new suburb to the city center by rapid transit.

Terminal Tower and Terminal Complex today (photo: Aerial Agents)

So, there was plenty to celebrate, as the $179 million project prepared to open.

But there were dark clouds on the horizon. Probably no one enjoying the glitz of the grand opening luncheon suspected that the Union Terminal’s opening would prove to be the high-water mark of Cleveland’s century-long rise. And not one of the many distinguished speakers hinted that Cleveland’s glory days were numbered.

A perceptive observer might have recognized a few ominous portends. The stock market crash of October 1929 had already shaved 33 percent off the market’s value. The number of unemployed workers in the city had jumped from 40,000 in 1929 to more than 100,000 in 1930, leaving more than a third of the city’s workers without jobs. During the 1920’s, passenger railroad traffic nationwide had dropped by 45 percent. Mass immigration had been ended by the First World War and anti-immigration legislation. City residents were moving to the suburbs in increasing numbers and manufacturing output had begun to decline. The many engines of Cleveland’s prosperity were grinding to a halt.

In retrospect, the signs were more than a dark smudge on the horizon. They were a tornado warning siren that couldn’t be turned off.

Today, Cleveland is still struggling to adapt to wrenching changes in America’s economy, decades of indifferent leadership, widespread disinvestment, racial animus, poverty, and the rest of the malevolent ills that have beset America’s former industrial heartland.

But the Union Terminal group still anchors a revitalized Pubic Square and the Terminal Tower still reigns as the city’s iconic symbol. The last passenger train left the station in 1977, but the terminal’s arched and columned concourses have been repurposed as a retail center and rapid transit trains still deliver thousands of passengers each workday. The department store is a casino now, but the hotel remains and the stately office buildings that comprised the bulk of the project still teem with workers.

The Van Sweringen’s railroad empire collapsed into bankruptcy in the mid-1930’s, but the steel, concrete, and marble evidence of their vision remains.

March 10, 2019

“If I must fall, may it be from a high place.”

Paulo Coelho, By the River Piedra I Sat Down and Wept