Enshrined in the National Housing Act (NHA) of 1934, redlining – the practice of denying loans to property owners within designated districts – fueled a deadly cycle of disinvestment, decay, depopulation, and decline in urban neighborhoods across the nation. The effects of redlining and other forms of institutionalized racism have been deep-seated and persistent and have continued despite the practice being outlawed by the 1968 Fair Housing Act.

Enacted in the depths of the Depression, the NHA was intended to stimulate housing construction to create jobs and improve the nation’s housing stock. But the benefits were intended for white Americans only, and the law encouraged lenders to deny loans to black, Hispanic, Asian, and foreign-born Americans.

Lenders weren’t required to evaluate loan applications based on the financial resources of individual applicants. Instead, federal officials rated city neighborhoods in a subjective and manifestly unfair manner, assigning each district one of four ratings: Best, Still Desirable, Definitely Declining, or Hazardous. Loan applications from areas rated ‘hazardous’ were automatically denied, regardless of the particular circumstances of the applicant or the condition of the property.

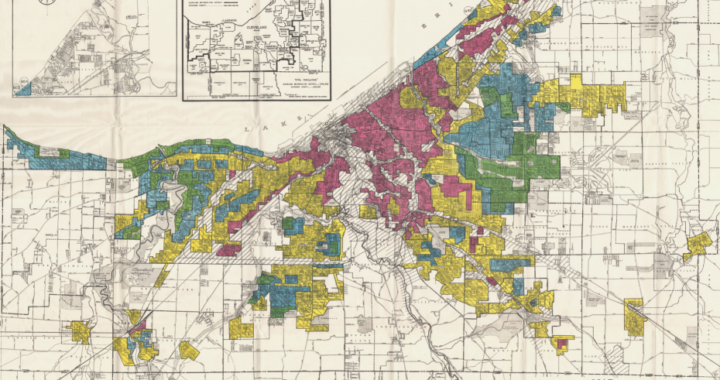

To help lenders, the government prepared color-coded maps of each of 239 American cities, showing the boundaries of each type of district. Zones rated ‘hazardous’ were outlined in red – hence the term ‘redlining’ – and no loans would be issued in those neighborhoods.

The ratings were based on a number of district-wide attributes, including the general condition, age, or state of repair of buildings as well as demographic data including population, class or occupation of residents, percentage of foreign-born residents, percentage of black, Hispanic, or Asian residents, and trends in economic or racial makeup of the population. A neighborhood with a growing black population, or a neighborhood that seemed likely to experience an increase in black residents, was said to be experiencing “Negro Infiltration.” That would ensure a hazardous rating and would virtually guarantee that no loans would be approved for purchase or upkeep of properties in the district.

The goal was to preserve property values and safeguard federal investments, as the government was guaranteeing the loans, said Brandon Crooks, co-founder of a New York City design studio that works at reversing the effects of redlining. Crooks was a panelist on a Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland virtual forum on redlining this week. Racism was literally baked into federal housing policies from the beginning, said Crooks.

Many neighborhoods that were rated hazardous were, in fact, stable, with occupied housing, thriving commercial districts, and strong local institutions. Yet they found themselves cut off from financing for repairs or mortgages. The results were catastrophic. Property values plummeted, neighborhoods declined, white flight accelerated, and housing segregation became entrenched.

Property owners in neighborhoods not redlined quickly understood that to preserve the value of their own properties they needed to keep black, Asian, and Hispanic residents out of their neighborhoods. Racial discrimination was already widespread in America – precisely the reason that integrated neighborhoods were redlined – but the explicit linkage of integration and declining property values ignited a cycle of rigid segregation that denied homeownership to millions of black Americans.

The closing of America’s housing market to black Americans – regardless of their level of education, employment status, and financial resources – has been a major contributor to the staggering gap in wealth between white and black Americans. In 2016, the net worth of a typical white family in America was $171,000 while the typical wealth for black families was $17,150.

That huge disparity cannot be attributed solely to redlining – 240 years of slavery, 150 years of housing and job discrimination, and 100 years of Jim Crow segregation all contributed. But since the Great Depression, homeownership has been the primary way that middle class American families have accumulated wealth. And that path was closed to black Americans for decades.

In 2019, 73.3 percent of white households owned their homes — compared to 42.1 percent of Black households, 47.5 percent of Hispanic households, and 57.7 percent of Asian or Pacific islander households that owned theirs.

In addition to the racial wealth gap, redlining has contributed to a host of ills that continue to afflict black Americans disproportionately, including worse health outcomes, predatory lending practices, higher rates of evictions, housing segregation, and problematic policing practices.

“Redlining was the original sin that so many of these impacts stem from,” said Jeniece Jones, executive director of Cincinnati’s Housing Opportunity Made Equal (HOME) organization.

The persistence of the wealth gap, despite many years of effort to close it, is a strong argument for some form of reparation payments for black Americans, said Cleveland State University professor Ronnie Dunn. “Reparations are the only way we will address the long-term harm of racially exclusionary and discriminatory practices,” he said.

February 17, 2021

For more information:

https://www.ally.com/do-it-right/home/what-is-redlining-how-does-it-impact-communities-today/