They needed a team of Navy SEALs. They got a 39-year-old lieutenant and two Korean intelligence officers.

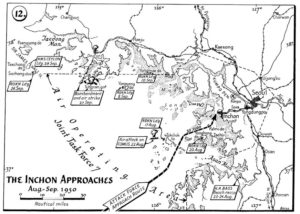

It was late August, 1950. The Korean War was two months old. Officers on General Douglas MacArthur’s Far East Forces staff were struggling to complete plans for an amphibious assault at Inchon. The invasion would land two American divisions in the rear of the North Korean People’s Army, which had pushed US and South Korean forces into a small toehold at Pusan.

Somehow MacArthur’s planners had scraped together enough ships, supplies, and men for the operation. But with less than three weeks left until the landing, planners knew next to nothing about the geography of the landing area, and what they did know was terrifying. A narrow ten-mile channel to the landing zones. Thirty-foot tides, a four-knot current. No beaches. Miles of mud flats. Had the North Koreans mined the approaches to the landing sites? Was the channel threatened by artillery? Was the area heavily defended? Could vehicles cross the mudflats? How strong was the current? Was the tidal range really 30 feet?

Inchon was occupied by North Korean troops. The South Korean government had fled in disarray. The American Far East command had never thoroughly surveyed the port. Charts and tide tables available in Tokyo were old and might be inaccurate. If a ship ran aground, struck a mine, or was disabled by shellfire in the narrow channel leading to the landing areas, the entire operation could fail.

They needed someone on the ground to survey the area, measure the seawalls, check the consistency of the mud flats, confirm the depth of the water, observe the tides, and locate defensive emplacements for pre-landing bombardments. Today, if satellite imagery and Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) flights couldn’t answer their questions, they would send a team of fabulously trained, expensively equipped, and ruthlessly determined Navy SEALS. In 1950, they sent LT Eugene Clark, a 39-year-old former Chief Yeoman assigned to the Geography Section of MacArthur’s Far East Command in Tokyo.

Right Down the Hall

While something less than an obvious choice, Clark did have a number of attributes that the planners valued. First of all, he was available. Right down the hall, in fact. Second, he had participated in amphibious landings against the Japanese during the Pacific War, so he knew the type of information the planners needed. Third, he had briefly served as captain of both an LST and an attack transport, so he was exceptionally familiar with the types of ships that would make the landing. Fourth, he had participated in clandestine operations along the Chinese coast, assisting the Chinese Nationalists in their civil war against the Chinese Communists. Fifth, he had been working on plans for the Inchon landing since July, so he knew the details of the assault. Sixth, he was – apparently – insanely courageous.

And, of course, there were no Navy SEALs in 1950. That program wouldn’t be established until 1962. During World War II, the US military had employed various amphibious scouting and Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) units to perform beach reconnaissance ahead of amphibious landings. Most such units were disbanded at the end of the war, but a handful of UDTs remained in service and two teams actually supported the Inchon invasion by landing ahead of the assault troops, scouting the mud flats, marking low points in the channel, clearing fouled propellers, and searching for mines.

But those operations wouldn’t happen until just hours remained before the landings, and MacArthur’s planners needed information now. So, on 26 August, they turned to Clark. The landing was scheduled for 15 September and Clark and whatever team he could assemble needed to be at Inchon by 1 September.

Approaches to Inchon

(Map from Naval History and Heritage Command)

No One-Night Stand

This would be no one-night recon operation: the plan was for Clark and a small team to set up a base on one of the islands in Inchon’s outer harbor. From there, they would conduct forays to the landing sites, reconnoiter other nearby islands, and obtain as much critical intelligence as they could from local residents and any prisoners they managed to capture. The fact that many of the harbor islands were already occupied by the North Koreans and that Clark and his team would have no boats of their own seemed not to matter.

Clark was no commando, and he had a comfortable job and family life in Tokyo. But he agreed to the mission, though he couldn’t tell his wife where he was going or how long he would be gone. For five days he worked with CIA planners at Far East Command headquarters to prepare for his mission. He would be accompanied by two Korean officers who had previously been assigned to the Far East staff: Korean Navy Lieutenant Youn Jong, and a former Korean counterintelligence officer, Colonel Ke In-ju.

LT Eugene Clark and Korean teammates on Yongung-do.

(Photo credit: http://www.koreanwaronline.com/arms/Clark.htm)

With no real idea of the situation they would encounter, Clark and the two Koreans collected a considerable arsenal of small arms, including .45 caliber pistols, submachine guns, rifles, hand grenades, and three .50 caliber machine guns from the armory at the Naval base at Sasebo, where a former shipmate of Clark’s was now the executive officer. They asked for mortars as well, but none were available. Time was short, Clark’s mission was urgent, and it was a simpler time. Clark’s former shipmate directed the base supply officer to provide everything on Clark’s list, and if there was something on the list they didn’t have, to get it from the army. They would fill out the paperwork later.

Sacks of rice, dried fish, tents, a shortwave radio, two cases of whiskey (to assist in extracting or purchasing information), and one million South Korean won (about $550 in US currency) were also packed. On 31 August, Clark and his team left Japan aboard a British destroyer. The next day, near Inchon, they transferred to a South Korean patrol craft, PC-703, for the final leg of their voyage.

South Korean patrol craft Sam Kak San (PC-703), formerly USS PC-802)

(Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval Historical Center.)

The PC was a former US Navy subchaser that had been given to the South Koreans and was armed with a 3-inch gun and several machine guns. The patrol craft would support Clark’s team through much of its 2-week mission. At that time, the North Koreans did not have naval craft of their own at Inchon, though they operated a number of armed junks and sampans. But the North Koreans had placed artillery on several islands and there was always a chance that they had mined the navigation channel, so the PC would have to operate with care.

So would Clark, but secrecy wasn’t part of his plan.

Building an Army

The first thing Clark did was land his team on an island several miles up the channel from Inchon. You might think they would have looked for a deserted island to keep their presence hidden from the North Koreans. Not Clark. Far from being uninhabited, the island he selected was home to 400 South Koreans and was occupied by a small detachment of North Korean Army troops, part of a garrison of 300 North Koreans based on a small island about a mile away. At low tide, it would be possible for North Korean soldiers to wade across the channel separating the islands. Within hours of landing, Clark and his team had killed four North Korean soldiers who were trying to escape by boat. It was certain, then, that North Korean troops would be back. It was just a question of when.

But Clark and his team had brought enough weapons to outfit a small army, and that’s what they started to do. Recruiting from among the hundred or so young men on the island, they created and armed an impromptu defense force which they hoped would be able to fend off any attacks until the invasion force appeared. They realized that there were probably Communist sympathizers on the island who would betray them to the North Koreans at the first opportunity, so they would try to guard against that, as well.

Stealing a Navy

Established on the island, their next task was to develop a plan for inspecting the landing sites, the channel, the mud flats, and the island of Wolmi-do, a rocky little peak that overlooked the landing areas and would have to be neutralized before the main landings.

With a need to get closer to Wolmi-do and Inchon, and without boats of their own, they simply stole a small fleet. Using a steam-powered fishing sampan belonging to an island resident that Clark christened “the flagship,” Clark and his team motored into the channel and seized a small flotilla of sail-powered sampans and junks.

Brought to Clark’s island base, the operators of most of the captured craft were happy to provide information about the channel, the tides, the currents, and North Korean defenses. Several offered to join Clark’s growing little band, and they were soon sent out on surveillance missions, examining the port of Inchon, Wolmi-do, and surrounding areas to look for signs of enemy troop concentrations and gun emplacements.

For the next week, Clark and his team gathered critical information and radioed it back to planners in Tokyo. But each night, North Korean infiltrators crossed over to his island. Some were killed, but Clark knew that an unknown number were now at large on his base.

Staying to the End

On September 7, British warships bombarded Inchon from the outer harbor. That night, a motorized sampan and three sailing sampans filled with North Korean troops were spotted in the channel heading for Clark’s island. Clark and his team quickly set out in their little flagship, hurriedly propping a .50 caliber machine gun atop sandbags. Although the powered North Korean vessel opened fire with an anti-tank gun, Clark bored in and destroyed the vessel and one of the sailing sampans with machine gun fire.

Back ashore, Clark radioed for assistance from PC-703, as he was certain that a heavier North Korean attack was imminent. But the next day, instead of the South Korean patrol craft, a U.S. destroyer, USS Hanson, appeared. Hanson had been ordered to evacuate Clark and his team, but, by now unsurprisingly, Clark refused. There was still a week before the invasion and he believed he could provide more critical information. Instead, he asked Hanson to bombard the island where the North Korean attackers were based.

USS Hanson (DD 832) supported LT Clark by shelling North Korean positions before the Inchon invasion.

(Photo credit: NAVSOURCE http://www.navsource.org/archives/05/pix2/0583232.jpg )

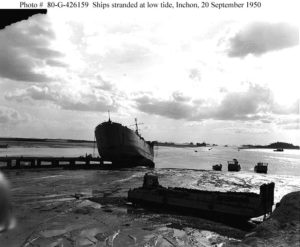

The shore bombardment bought Clark some time, and for the next few nights he and his team surveyed Inchon and tested the mud flats to see if they would support vehicles. They wouldn’t, and Clark sent that info on to Tokyo. He also informed planners that Japanese tidal charts were more accurate than the charts the Americans had prepared and he sent information on the placement of artillery on Wolmi-do. One of his sampans even towed a handful of floating mines out of the navigation channel.

Clark’s reports were forwarded to strike planners and soon Wolmi-do was plastered with explosives from US ships and aircraft.

Lighting the Beacon

Finally, 14 September arrived. That night the invasion would begin. Earlier, Clark had figured out how to relight the channel lighthouse on Palmi-do island and had offered to do so. Invasion planners had asked him to light the beacon at midnight on the 14th. But late that day, as Clark was packing his gear, his lookouts spotted more than 400 North Korean troops approaching by boat and on foot, wading across the narrow channel.

There was no chance that Clark and his ragged self-defense force could beat back this attack. Clark hastily organized a delaying force and ordered everyone else to escape by boat while he and his original teammates made their way by sampan to Palmi-do and its lighthouse.

Sometime after midnight, Clark managed to relight the lamp in the lighthouse and the invasion was a spectacular success. The next morning, Clark and his South Korean lieutenants made their way to the force flagship, where they reported the end of their mission. Clark begged the staff to order troops to his former island base, to rescue the civilians that had refused to evacuate and the defenders that had stayed behind.

Low tide at Inchon.

(Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.)

They Paid the Price

But it was 24 hours before Marines could be spared to take the little island. By then, the North Koreans had not only overrun the few defenders that remained, they had also executed at least fifty villagers that they suspected of helping the Americans.

Eugene Clark received the Silver Star for his efforts at Inchon. During his two-week mission, the sleep-deprived and exhausted Clark lost 40 pounds. That might have been enough for most officers. But Clark was not most officers.

For the next two months he led a series of South Korean guerilla raids along the coast of North Korea, gathering intelligence and capturing small islands that the Americans would use to rescue pilots who had to ditch damaged aircraft. On October, working near the mouth of the Yalu River, Clark’s Korean agents reported that the Chinese were massing for an enormous attack against the UN forces. Clark sent a warning to Tokyo, but his warning, like so many others, was discounted and the eventual Chinese offensive drove the unprepared UN forces south past Seoul.

In 1951, Clark led one final commando-style raid, as he and a small team came ashore at Communist-occupied Wonsan to find out if rumors of an outbreak of bubonic plague were true. Clark’s team penetrated a Chinese Communist hospital and the team doctor examined two patients, who turned out to have smallpox, not plague. That information saved UN forces the formidable task of inoculating hundreds of thousands of soldiers against plague. This mission earned Clark a Navy Cross.

Clark retired from the Navy in 1966, having risen to the rank of commander. He died peacefully in 1968.

March 25, 2019

For a full recounting of LT Clark’s mission, see The Secrets of Inchon, by CDR Eugene Clark, USN; P. Putnam’s Sons, NY; 2002.