He didn’t free the slaves, but he offered them a glimpse of a better future.

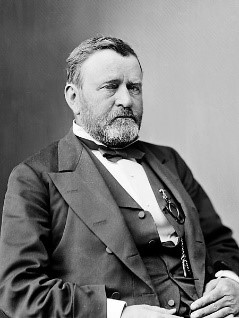

Ulysses S. Grant, who served as president from 1869-1877, is best known as the Union general who finally defeated Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia, effectively ending the Civil War. Grant is also acclaimed for his earlier victories at Ft. Donelson, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. Grant’s presidency has not been highly regarded, as his two terms were marred by corruption among appointed officials and a faltering economy.

But his reputation is rising. Grant has always been recognized for his personal honesty, and historians today are increasingly crediting Grant with courage and moral resolve for his efforts to protect the rights of freedmen – freed slaves.

Grant took office following the highly contentious administration of Andrew Johnson. By Grant’s inauguration seven of the eleven Southern states which had formed the Confederacy had been re-admitted to the union and the four remaining states would be re-admitted in 1870. But while southern states rejoined the union, they fiercely resisted efforts by Republicans, both northern and southern, to grant the rights of citizenship to the freed slaves.

Upon taking office Grant began receiving a steady stream of letters begging for federal help in protecting southern blacks and white Republicans from the nightriders of the Ku Klux Klan and other terrorist organizations. Southern Republicans reported that a “reign of terror” was spreading across the south, with blacks and whites being murdered with impunity.

Northern Democrats joined Southern Democrats in opposing any federal action to protect the rights of freedmen, and, of course, the newly formed state governments were dominated by whites who were happy to use intimidation and violence to preserve the pre-war social order. Meanwhile, Northern Republicans were exhausted by the unending sectional strife and were increasingly content to ignore Southern depredations.

Grant quickly recognized that the governments of the southern states were unwilling to protect blacks and southern Republicans, but he did not believe that current federal law gave him the authority to intervene. So, he sought and received additional powers through legislation, including the 1871 “Act to Enforce the Provisions of the 14th Amendment,” popularly known as the Ku Klux Klan Act.

The Act gave the federal government the power to prosecute state officials for civil rights violations in federal courts and to suspend habeus corpus when state authorities were unable or unwilling to protect civil rights.

Passage of the law gave Grant the tools, but he still needed to supply the moral and political will to use that power. That he did so is to his everlasting credit. Grant suspended habeus corpus in nine counties of South Carolina and dispatched federal troops and marshals. Federal forces identified and arrested hundreds of KKK terrorists, while many others fled the state. Grant’s actions broke the power of the Klan and other violent groups in South Carolina and the demonstration of federal power and resolve crippled Klan efforts across the south. Political violence in South Carolina and throughout the south declined dramatically.

But while overt violence was reduced, preserving white supremacy remained the highest priority of local governments throughout the south, and they eventually succeeded in disenfranchising black voters and imposing a brutal regime of legal segregation. Black Americans in the former Confederacy wouldn’t regain the basic rights of citizenship until the federal government again stepped forward in the 1960’s.

Grant’s impact was recognized by many of his contemporaries, including Frederick Douglas, who wrote, “To [Grant] more than any other man the negro owes his enfranchisement and the Indian a humane policy. In the matter of the protection of the freedman from violence his moral courage surpassed that of his party; hence his place as its head was given to timid men, and the country was allowed to drift, instead of stemming the current with stalwart arms.”

Douglas quote: http://thepresidentsatbigmo.blogspot.com/2007/10/number-18-ulysses-s-grant.html

Grant photo: Library of Congress / https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ulysses_S._Grant_1870-1880.jpg

April 27, 2018