On March 9, 1862, the U.S. Navy ironclad gunboat USS Monitor fought a four-hour duel against the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia. But the historic encounter – celebrated as the world’s first combat between ironclad warships – might have been just the second-worst thing to happen to the Monitor’s crew that week.

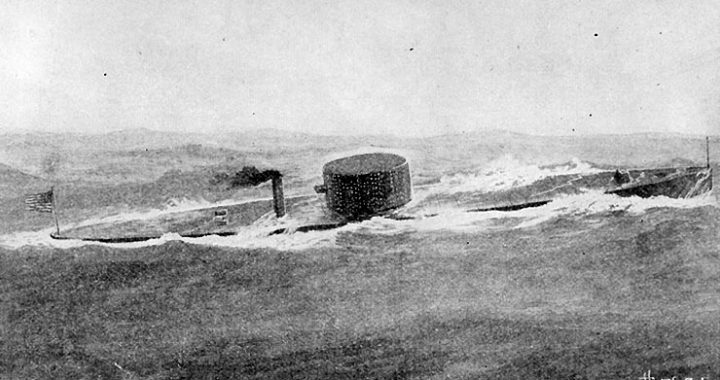

(Naval Heritage and History Command photo)

Sure, the battle itself was a terrifying affair, as Confederate shells repeatedly banged off the Monitor’s armored turret. One exploding shell struck the Monitor’s exposed pilot house, temporarily blinding the union warship’s captain. Inside the ship, the crew fought in smoky semi-darkness, seeing nothing and hearing little except the deafening crash of their own cannons.

But just getting to the battle tested the Monitor’s crew like few other voyages in U.S. Navy history.

For two days the union crew had endured a howling North Atlantic gale, repeated mechanical breakdowns, poisonous gases, exhaustion, and no hot coffee. A couple of hours of steadfast combat against the Virginia must have seemed anticlimactic to the sweating, straining sailors aboard the Monitor.

Hastily constructed in response to reports that the Confederates were converting the former USS Merrimack into the ironclad Virginia, Monitor was authorized and built in an astonishing 100 days. The design, by Swedish-born engineer John Ericsson, included forty patented inventions and featured a rotating turret that eliminated the need to turn the vessel to bring its main guns – actually, its only guns – to bear, a revolutionary advantage for combat in enclosed, shallow waters, like Hampton Roads.

The innovative design captured the imagination of Abraham Lincoln, who urged the Navy to acquire the vessel, but did not exactly thrill the members of the Navy’s Ironclad Board, who were to select the design. They made sure that the contract for the ship included a money-back clause if the ship proved to be a failure. They also required that the vessel be equipped with masts and sails, which was probably prudent in those early days of steam power. In the end, the Board approved the design primarily because the ship would be relatively cheap and could be ready in just over three months.

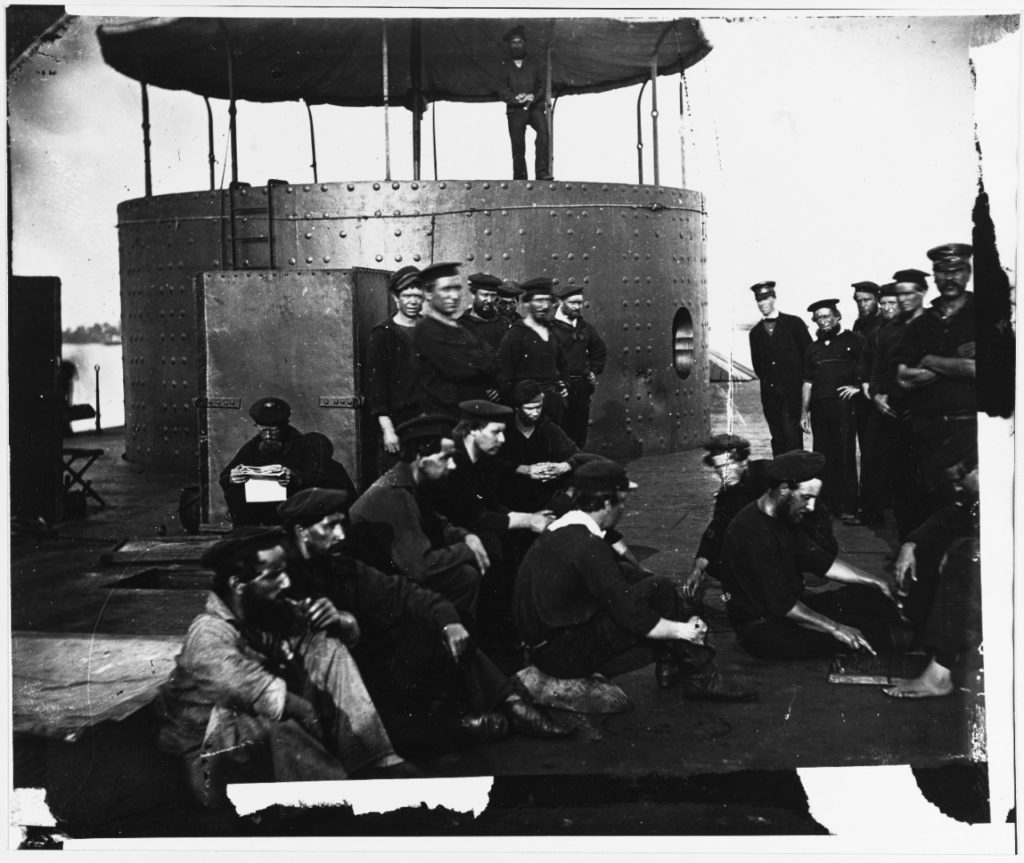

Constructed in Brooklyn, NY, USS Monitor was launched on January 30, 1862. The crew, hastily assembled as well, but presumably unfazed by their ship’s money-back guarantee, quickly set to work learning to operate their futuristic warship.

By February 19 the crew was ready to get underway for trials. The ship, perhaps, not so much. During its initial outing, engine problems forced the Monitor to be towed back to the yard. But the problems turned out to be minor, or, at least, could be repaired quickly, and Monitor was commissioned on February 25, 1862. She was immediately ordered to sail to Hampton Roads to defend the Navy’s wooden blockading vessels from CSS Virginia.

But as the ship left New York, it was quickly discovered that the steering gear had been improperly installed. Back at the yard, reinstallation was completed by March 6. By then, the money-back guarantee must have been looking more and more like a wise investment.

In an account dictated near the end of his life in 1916, Monitor veteran John Driscoll described his ship’s departure from New York as “nothing but gloom.”

But gloom would soon give way to something more akin to terror.

Towed by a sea-going tug and escorted by a pair of Navy steamships, which Driscoll noted would be totally useless in case trouble overtook the Monitor, the ironclad set off for Hampton Roads on March 6.

The first day was uneventful, although the weather became increasingly threatening. By evening of the second day, a full-force gale engulfed the little convoy. Monitor, with just two feet of freeboard, was singularly ill-designed to weather an ocean storm.

Almost immediately pounding waves swept the deck, and seawater poured into the ship through the smokestacks and blower pipes. While the engine room crew struggled to stay upright in their bouncing, iron ship, they were startled to see the belt fly off the port blower engine, reducing ventilation in the enclosed ship by half. Engineers shortened the belt, but every attempt to replace it failed, as the fan box had filled with water, preventing the engine from starting and flinging off the belt. As the engineers struggled with the port belt, the belt on the starboard blower engine also flew off, leaving the engine room with no ventilation at all.

Unsurprisingly, the engine room quickly filled with exhaust gas, felling all nineteen men in the space. Quickly, other crewmembers rushed into the engine room and dragged their shipmates to safety.

Not exactly safety, perhaps, as the ship remained in the grip of the gale and the blowers were still inoperative. But at least they could breathe the air in the turret, where they were taken to recover.

Driscoll had not been in the engine room when the blowers failed, so he had not been affected by the gas. Covering his mouth with a wet handkerchief and keeping his face as close to the deck as he could, he made his way into the gas-filled space and attempted to restart one of the blowers. Immediately, the belt flew off. Realizing that the flooded boxes were the problem, Driscoll grabbed a hammer and chisel and punched a hole in the fan box, allowing the water to drain out. In his words, the flood of water rushing over him expelled the gas near his face, allowing him to take a few short breaths. With the water removed, the belt stayed put and the blower started.

With one blower running, the gas was soon expelled from the engine room, and Driscoll, fortified with a shot of medicinal brandy and assisted by several seamen, re-entered the space and restarted the other blower. With that, the immediate crisis passed and Monitor continued on her way to Hampton Roads.

Throughout the voyage, water entering the ship through the vents and the turret made cooking impossible. Nearly fifty-five years later, Driscoll still ruefully recalled, “We had not even a cup of coffee from Friday morning until Sunday morning; we had cold water and hardtack.”

Monitor arrived at Hampton Roads late on March 8, after the Virginia had already sunk two Union warships, killing more than 400 U. S. Navy sailors.

Through the night and early morning. Monitor’s crew prepared to face the Virginia. They went into combat with guns that were untrusted and scarcely tested. Because the Monitor’s turret was barely larger than the guns, a recoil dampening mechanism had been invented by Ericsson. During initial testing of the guns, the brake mechanism was inadvertently loosened, allowing the guns to smash into the rear of the turret after firing, leaving dents that are still visible today on the recovered ship. More importantly, fears that the weapons would explode if a full charge of powder was used forced the crew to limit the amount of powder in each shot. Afterward, engineers estimated that if full charges had been used, Monitor’s shells would likely have penetrated Virginia’s armor.

As it was, neither Monitor nor Virginia could seriously damage their ironclad opponent, and Virginia eventually steamed away. She did not return to threaten the blockading fleet. Monitor’s mission of defending the blockading vessels from Virginia was fulfilled.

March 9, 2019

For more, see:

https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2012/april/last-union-survivor