The war was going badly for the North Koreans, and it was about to get worse.

It was September 14, 1950, more than 11 weeks after North Korea’s June 25 invasion of South Korea. The North’s military planners had expected that it would take just four weeks to crush the Republic of Korea (ROK) army and reunify the peninsula under the communist government of Kim Il-Sung. But now it was mid-September and South Korean forces and their American allies still held a toehold around the port of Pusan. A last-gasp North Korean offensive had failed to break the ROK/U.S. lines.

North Korea was not prepared to fight a long campaign, especially against an enemy that had complete control of the air and sea.

At first, the invasion had gone exactly as planned. North Korea’s army was better equipped, better trained, and more experienced than South Korea’s forces, and the communists had quickly smashed through the southern defenses and driven the disorganized and demoralized survivors 150 miles south toward the tip of the peninsula where they would surely be trapped and annihilated.

But North Korea’s timetable had been upended catastrophically when the United States intervened with air, sea, and ground forces. Neither the North Koreans, nor the Soviets and the Chinese, who had both reluctantly agreed to support the invasion, believed that the United States would respond to the North Korean attack with military forces of its own.

A Shocking Decision

But within 72 hours of the invasion, President Truman, erroneously believing that the Soviet Union had ordered the invasion and fearing that it might be the opening move in a world-wide communist offensive, had ordered U.S. air and naval forces to intervene. Three days later he ordered American ground forces into action, shocking the North Koreans and their patrons. On July 3, 1950 American carrier-based planes launched their first strikes against North Korean targets and within weeks were attacking North Korean troops pushing south. U.S. ground forces – although shamefully ineffective at first – arrived in increasing numbers and showed increasing competence. Supplies and reinforcements flowed through Pusan and the U.S. and ROK forces gained strength, finally halting the North Korean advance near Pusan. The objective of the North Korean invasion plan was to smash the ROK forces and occupy the entire country before the United States could rearm or resupply their ally. But they hadn’t expected the U. S. to join the fighting.

One Last Push

On September 1, weeks after the war was supposed to be over, North Korea had launched its last big push against the U.S. and ROK lines surrounding Pusan. For their Naktong offensive, the North Koreans threw everything they had left at the U.S. and ROK defenders. It wasn’t enough.

Two months of steadily increasing U.S. air attacks against North Korean supply lines and stiffening resistance by American and South Korean ground forces had bled the North Korean army dry. To launch their attack, they had stripped defending troops from most of the key places they had captured, including the port of Inchon, and thrown thousands of untrained conscripts into battle.

Though weakened by horrific casualties and shortages of food, ammunition, and fuel, the North Korean attackers pushed forward grimly. Initially they made encouraging gains, and in a few places they actually broke through. But American and South Korean forces patched the breaches and threw the North Koreans back. With U.S. and ROK forces growing stronger, and the North Koreans reeling, it looked like the next phase of the war would be a United Nations offensive that would break the siege of Pusan and force the North Koreans back up the peninsula’s harsh terrain, one bloody mile after another.

The North Koreans were exhausted, outnumbered and running out of everything, including time. They were facing complete destruction, and neither the Soviets nor the Chinese were willing to provide military forces.

Worse, they knew that the Americans and their United Nations allies were preparing for an amphibious landing and they had no way to prevent it.

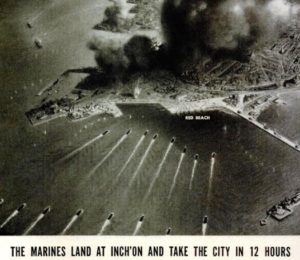

The UN landing – codenamed Operation Chromite – would take place on September 15 at the port city of Inchon, halfway up the Korean peninsula on the Yellow Sea. Planned by the American General Douglas MacArthur in his role as United Nations commander, the invasion would succeed brilliantly and lead directly to the rout of the North Korean army.

Because the landing was so successful and was accomplished at such low cost to UN forces, many observers have assumed that the North Koreans were surprised. That was hardly the case. In fact, the landing at Inchon was one of the worst-kept secrets of the Korean War.

Operation Common Knowledge

It didn’t take any actual espionage to realize what MacArthur was planning. First of all, an amphibious landing behind the North Korean lines was a glaringly obvious maneuver, especially since UN forces had complete air and naval supremacy. MacArthur himself had conducted dozens of similar landings during World War II to bypass Japanese strongpoints on New Guinea and in the Philippines. His belief in the value of an amphibious capability was so strong that he made certain the Far East forces he commanded from Japan were trained to conduct amphibious operations.

Before the war was one week old, MacArthur had ordered his staff to begin planning an amphibious assault behind the North Korean advance at Inchon to relieve pressure on the retreating ROK/U.S. units. That landing, codenamed Operation Bluehearts, was to have taken place before the end of July.

But the North Korean advance was so rapid, the performance of the retreating ROK troops so lacking, and the combat readiness of the U.S. forces that had been hastily dispatched to Korea from occupation duty in Japan so abysmal, that by the end of July the North Koreans were threatening to push the ROK/U.S. forces right off the peninsula. MacArthur had to turn his immediate attention to holding Pusan and its priceless port, without which the war could not be won.

So Bluehearts was canceled, but would soon be resurrected as Operation Chromite, once the ROK/U.S. position at Pusan was stabilized. By the beginning of August, MacArthur began planning Chromite in earnest.

MacArthur needed troops, transport ships, landing craft, and supplies for a major landing, and there was no way to get them without the help of hundreds of military and civilian planners, logisticians, and schedulers from staffs in Tokyo, Pearl Harbor, Washington DC, and allied capitals. Hundreds of civilians in Japan and other locations were being contracted to provide supplies or services in support of the operation. The recall of Marine reservists, the stockpiling of supplies, and preparations to use Japanese-crewed landing ships for the assault ensured that even the most obtuse observer could divine what was about to happen. Operational security was so compromised that American officers in Tokyo began referring to the planned landing as “Operation Common Knowledge.”

Mao’s Warning Ignored

Alarmed by the massive build-up of troops and ships, two weeks before the Inchon landing China’s Mao Zedong warned Kim to prepare for a landing at Inchon and urged him to strengthen defenses there. But Kim told a Chinese emissary that the North Koreans did not believe that the UN forces had the strength to mount an amphibious landing.

Whatever strength MacArthur could muster, it was clear, though unstated, that North Korea lacked the strength to defend Inchon and simultaneously break the ROK/American lines at Pusan. Documents captured at Pyongyang later in the war showed that the North Koreans knew about the landing at Inchon before the end of August, but could do little to stop it. They had already stripped their defenses there and almost everywhere else to reinforce their offensive at Pusan, and those troops weren’t coming back. Although the North Koreans had plans to mine the harbor at Inchon, they never got to it. But even unmined and nearly undefended, Inchon was going to be no easy task for the Americans.

The Worst Possible Place

While MacArthur’s decision to conduct an amphibious landing might have been more conventional wisdom than genius, his fierce conviction that Inchon was the one place where the landing must occur was, in fact, a masterstroke. MacArthur could not have found a physically less suitable landing area for an amphibious attack if he had searched for ten years. Everyone who knew what Inchon was like was aghast. But MacArthur believed that landing at Inchon would place his forces in the best position to cut the North Korean supply lines and crush the North Korean army besieging Pusan. His eloquent and powerful defense of the plan persuaded the skeptics – which included his nominal bosses on the Joint Chiefs of Staff – and eventually the landing was approved.

Not that the skeptics were wrong. Inchon really was a terrible place for an amphibious landing. For one thing, there were no actual beaches. The landings would have to be made against stone sea walls which rose as high as eight feet above the decks of the landing craft, forcing assault troops to use ladders to get ashore. The only possible landing zones were in the heart of the city, which meant that once ashore, MacArthur’s troops would immediately be faced with the possibility of building-to-building combat, a type of warfare that heavily favored the defenders and seemed certain to trap the Marines in a bloody urban battle of attrition.

Landing ships could only approach the sea walls at maximum high tide, which only occurred twice each month. At all other times the approaches to the shore were blocked by miles of impassable mud flats. Tides at Inchon ranged from an average of 23 feet to a maximum of 33 feet and the current in the channel reached eight knots. The two landing “beaches” were located on either side of the main port, more than four miles apart, forcing the Americans to split their forces at the outset.

The city itself was located miles from the open sea and could be reached only after navigating a narrow 10-mile long channel, which could be mined and defended by shore batteries. Near the city the channel was protected by a rugged little island called Wolmi-Do that would have to be captured prior to the main landing, thus ensuring that the North Korean defenders were alerted.

As one naval officer involved in the planning famously recalled, “We drew up a list of every natural and geographic handicap—and Inchon had ’em all.”

Building the Force

But these obstacles were only part of MacArthur’s problems. First, he had to come up with a landing force and ships to bring them ashore. In the five years since the end of World War II, the United States had junked the most successful and best-equipped amphibious force in history. By the time North Korea invaded the south, the U. S. Marine Corps had shrunk from 474,000 marines in 1945 to just over 75,000 in 1950. The Navy’s demobilization of its amphibious fleet was even more drastic, plummeting from 3,000 ships in 1945 to 148 in 1948.

MacArthur needed more than 40,000 men for his planned assault and most of the readily available combat troops had already been sent to bolster the forces fighting at Pusan. To find two more divisions of troops, the Joint Chiefs would have to dip into America’s strategic reserve, reducing the nation’s ability to fend off another attack elsewhere.

But the chiefs and the president agreed, and by recalling thousands of Marine reservists, rebuilding the Army’s half-strength Seventh Division by stripping units from other commands, increasing America’s military personnel limits, and augmenting the Seventh Division with 8,000 untrained South Korean conscripts, the Joint Chiefs found the troops MacArthur needed.

The Navy didn’t have enough active landing ships in the Pacific to bring the two divisions ashore, so MacArthur assigned fifteen LSTs and two cargo ships that had been turned over to the Army in 1945 to support the occupation forces. These ships had been decommissioned from the Navy and were operated by Japanese crews, much of the specialized equipment needed for a landing had been removed and they were in deplorable condition, but they would have to do. The Navy quickly recommissioned the ships, made some hasty repairs, assigned new commanding officers – although most were frighteningly inexperienced – and added a few signalmen and quartermasters to the Japanese crews to assist with communications and beaching operations. Smaller landing craft were brought out of storage and reactivated and experienced sailors were flown out from the United States to operate them.

In the end, MacArthur’s Inchon assault force included the First Marine Division, the Seventh Infantry Division, several units of ROK troops, and Corps-level support units, including artillery; supported by a multi-national naval force of 261 ships including amphibious ships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, fire support ships, and minesweepers.

There would, of course, be no time for a rehearsal, and many of the troops were scarcely trained, but though hastily planned, the landing was superbly executed. Less than 90 days from North Korea’s surprise invasion, MacArthur, the U. S. and ROK militaries, and a handful of allies had turned back the North Korean attackers at Pusan and delivered a powerful counterstroke at Inchon.

Another Chinese Warning

As MacArthur had predicted, the landing faced little opposition and U. S. casualties were light. Despite receiving explicit warnings from the Chinese that a landing at Inchon was possible, the North Koreans had gambled that they could crush the UN forces at Pusan before the Americans could land at Inchon and failed to establish an adequate defense. Within ten days of the landings the Marines recaptured Seoul.

At Pusan, the strengthening UN forces launched an offensive on 16 September and within days were driving the North Koreans northward. Trapped between the two UN forces, the already-weakened North Korean army collapsed with astonishing speed. Fewer than 40,000 stragglers made their way, without equipment, back to North Korea.

The suddenness of the North Korean collapse made the reunification of North and South Korea under the South Korean government look temptingly easy, and despite receiving their own explicit warnings from the Chinese, the Joint Chiefs and President Truman gave MacArthur permission to invade the North.

But the Chinese weren’t bluffing. They would not accept a reunified Korea that was allied with the United States. As MacArthur’s forces charged north, Chinese troops flowed south. By late October, some ROK patrols had reached within a few miles of the Yalu River, the boundary between North Korea and China. On November 25 the Chinese attacked with overwhelming force, driving the U.S. and ROK forces south, over the South Korean border and beyond. Seoul, or what was left of it after being captured and liberated during the summer, was captured again.

Finally, the UN forces stiffened, and slowly pushed the North Koreans back. Once the UN forces had forced the Chinese back into North Korea, the exhausted armies of both sides settled in for a bloody two-year stalemate that was finally ended by an armistice in 1953.

“We shall land at Inchon and I shall crush them.”

– GEN Douglas MacArthur, 23 August 1950

October 11, 2019